Lifecycle of Personal Data Under the DPDP Act

Personal data does not just exist inside organisations.

It moves, changes hands, ages, and eventually must disappear.

Yet most DPDP compliance failures don’t happen because organisations ignore the law. They happen because organisations fail to manage the lifecycle of personal data end-to-end.

This blog breaks the Lifecycle of Personal Data under the DPDP Act, 2023 into clear, enforceable stages – and shows how compliance must be engineered, not documented.

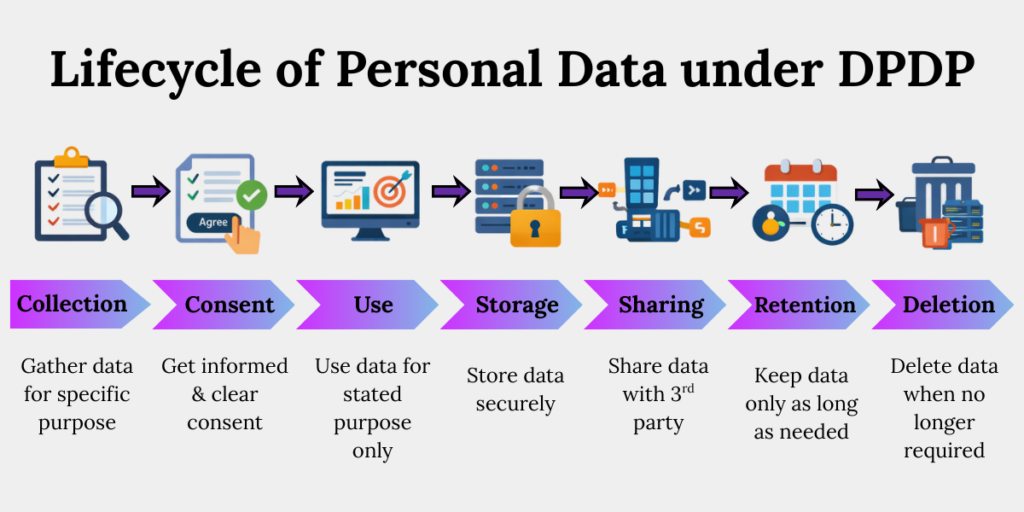

Understanding the Lifecycle of Personal Data Under the DPDP Act

Under the DPDP Act, personal data is regulated across its entire lifecycle – from collection and use to storage, sharing, retention, and deletion. Compliance is continuous, not event based. Obligations apply at every stage, and failure at any one point can trigger penalties, enforcement action, or loss of trust.

Think of personal data like a secure facility, not a file folder.

If even one gate is left open, the fortress fails.

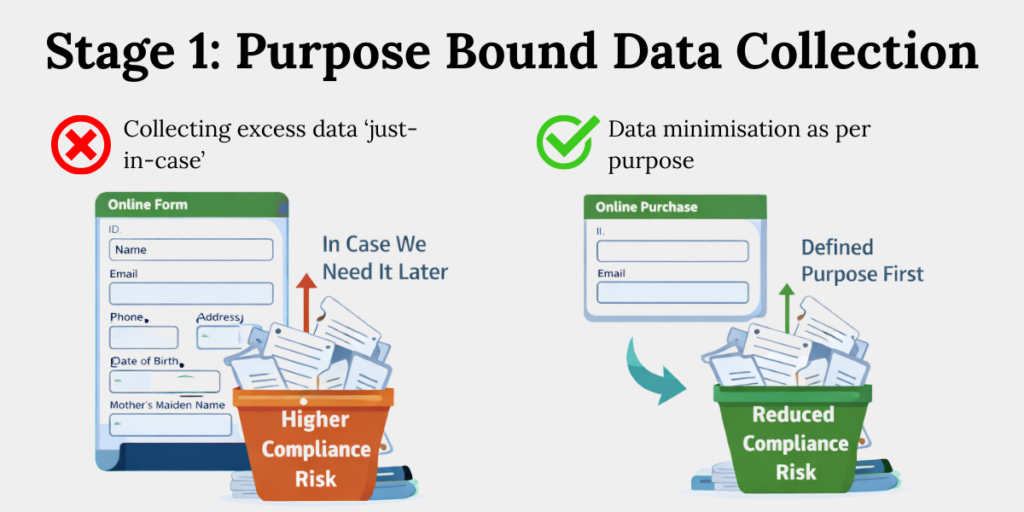

Stage 1: Personal Data Collection Must Be Purpose-Bound

Section 4 to 7 of the DPDP Act permits collection of personal data only for a clear, lawful, and specific purpose with valid consent or a notified legitimate use. Excessive or speculative data collection increases regulatory exposure without adding business value.

Most organisations collect data just in case.

DPDP breaks that habit – hard.

In practice:

- Define the purpose first

Before designing any form, clearly decide why you need the data. This purpose should be specific enough that a regulator, or a user – can easily understand how the data will be used.

If the purpose is unclear, the collection itself becomes hard to defend. - Collect only what’s necessary

Every field on a form should directly support the stated purpose. If a data point does not actively help deliver that purpose, it does not belong there.

Less data reduces compliance risk and operational exposure. - Record the reason for each data point

Maintain a simple internal note explaining why each piece of personal data is collected. This documentation helps teams stay consistent and becomes critical during audits or breach investigations.

If you cannot explain why you collected it, you cannot justify keeping it.

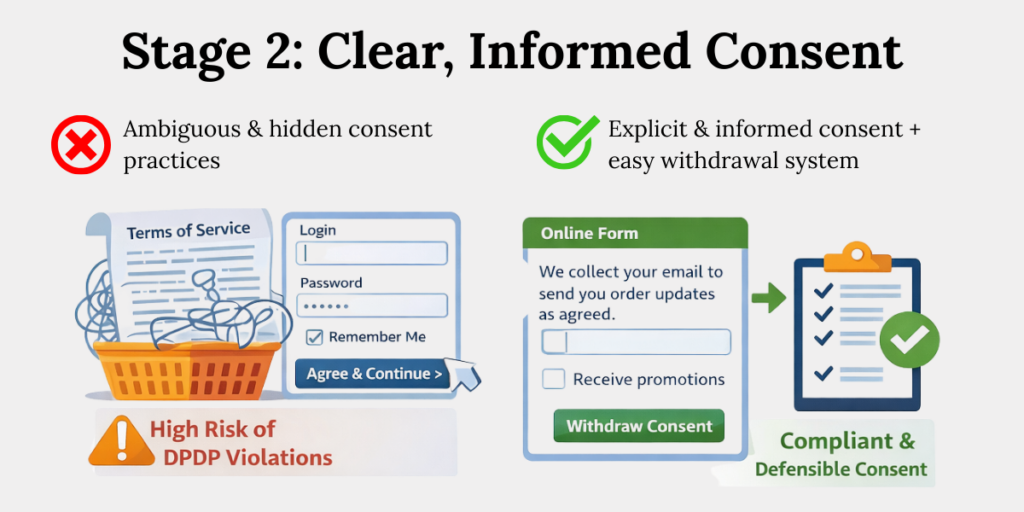

Stage 2: How Consent and Notice Work Under the DPDP Act?

According to the DPDP Act, Section 6, consent must be free, informed, specific, unconditional, and unambiguous, supported by a clear notice. Pre-ticked boxes, bundled permissions, or vague language invalidate consent. Withdrawal must be as easy as giving consent.

Consent is not a checkbox.

It’s the front gate of your data fortress.

Operational checklist:

- Keep consent separate

Consent should not be buried inside terms and conditions. Users must be able to clearly see what they are agreeing to and make a real choice.

Mixing consent with legal text weakens its validity under the DPDP Act. - Explain the purpose clearly

Tell users why their data is being collected in simple, everyday language. Avoid legal or technical jargon that hides the real use of the data.

If a user cannot easily understand it, the consent is likely not informed. - Make withdrawal easy

Withdrawing consent should be as simple as giving it. Users should not have to email multiple teams or follow complex steps to opt out.

Difficult withdrawal processes are a common compliance failure. - Record how consent was given

Keep basic records of when and how consent was collected, and for what purpose. This helps prove compliance during audits or complaints. Without records, consent is hard to defend.

In our observation, consent failures are the fastest path to DPDP violations.

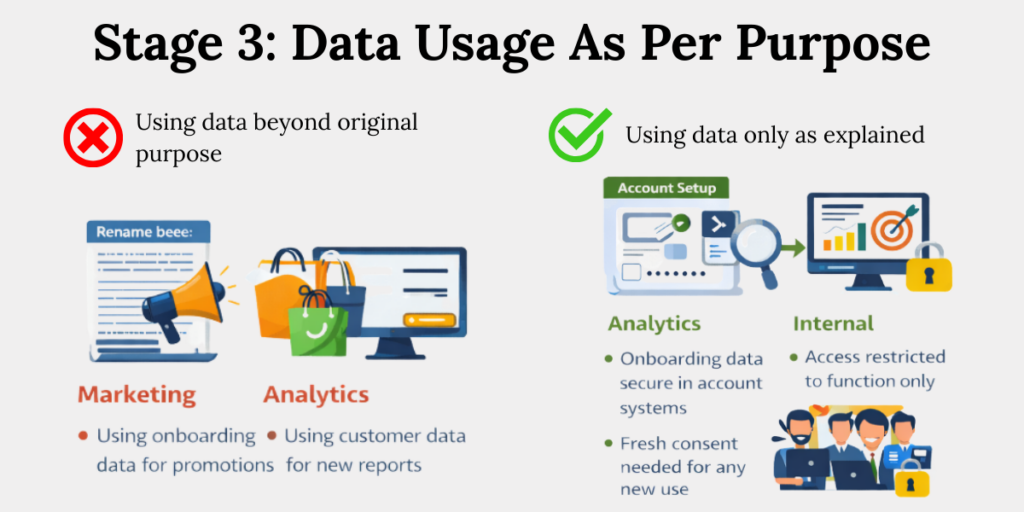

Stage 3: Personal Data Use Must Stay Within Declared Purpose

Personal data may only be used for the purpose disclosed at the time of collection unless fresh consent or legal authority exists. Function creep – using old data for new objectives – is a direct DPDP compliance breach.

Data misuse rarely looks malicious.

It usually looks convenient.

Common risk patterns:

- Marketing reuse of onboarding data

Data collected for account setup is often reused for promotions or campaigns. This usually happens without fresh consent. Under DPDP, this counts as using data beyond its original purpose. - Analytics expanding data use

Analytics teams may start using existing data for new insights or reports. If this new use was not explained earlier, it requires a consent refresh. Convenience does not replace compliance - Uncontrolled internal access

As teams grow, more employees gain access to personal data than necessary. This increases the chance of misuse or breaches. Access should always be limited to what a role genuinely needs.

Purpose limitation is not a policy – it’s an operating constraint.

Stage 4: What Security Measures Does the DPDP Act Require?

The DPDP Act Section 8 requires Data Fiduciaries to implement reasonable security safeguards to prevent breaches. What is “reasonable” depends on data sensitivity, scale, and risk – not organisational comfort.

Security is not an IT function alone.

It’s organisational discipline.

Practical safeguards include:

- Limit access by role

Employees should only access personal data needed for their job. This reduces accidental misuse and makes it easier to trace responsibility if something goes wrong.

Broad, shared access is a common security failure. - Encrypt data everywhere

Personal data should be encrypted when it is stored and when it is being transferred. This ensures that even if systems are compromised, the data remains unreadable.

Encryption is now a basic expectation, not an advanced control. - Track and review access

Systems should log who accessed personal data and when. These logs must be reviewed regularly to spot unusual or unauthorised access. Without monitoring, access controls lose their value - Align vendor security standards

Vendors handling personal data must follow the same security standards as the organisation. Contracts should clearly define security responsibilities and breach reporting timelines.

Weak vendor security often becomes the weakest link in compliance.

Based on recent enforcement trends, weak internal access controls trigger disproportionate penalties.

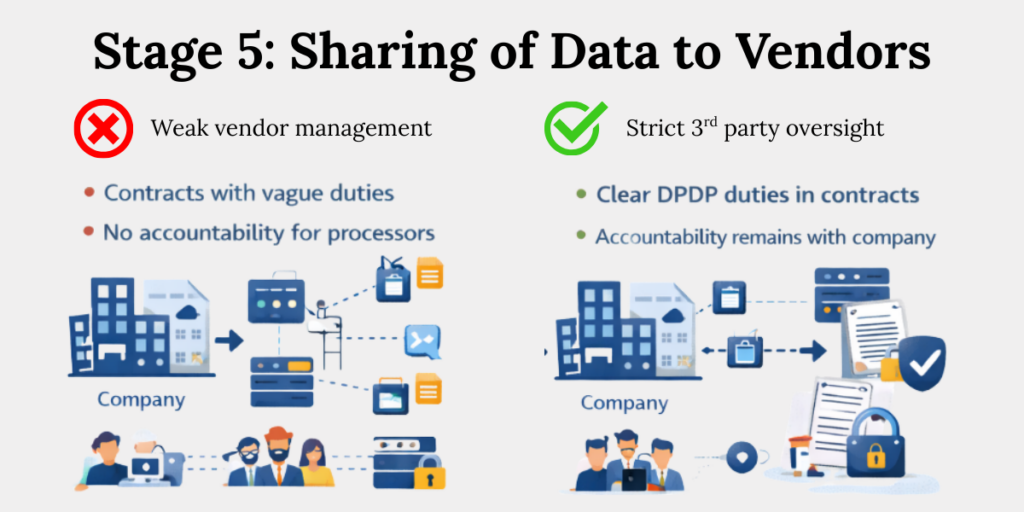

Stage 5: Data Sharing Extends, Not Transfers, Liability

According to Section 16 of the DPDP Act, when personal data is shared with processors or vendors, the original Data Fiduciary remains accountable. Cross-border transfers are allowed unless restricted by government notification, but responsibility never transfers.

Outsourcing does not outsource liability.

What strong organisations need to do:

- Maintain live vendor data maps

Keep an up-to-date record of which vendors receive personal data, what type of data they access, and why. This map should reflect reality, not just contracts. If data flows change, the map must be updated immediately. - Enforce DPDP duties through contracts

Vendor contracts should clearly state DPDP obligations such as security standards, breach reporting, and data deletion. Verbal assurances are not enough. If it is not written into the contract, it is hard to enforce. - Audit how processors access data

Regularly check how vendors actually access and use personal data. This helps catch risky practices early, before they turn into violations. Audits do not have to be complex, but they must be consistent. - Track sub-processors

Know if your vendor is passing data to other third parties. Sub-processors often sit outside direct visibility but carry the same risk. Lack of awareness here is a common compliance blind spot.

If you don’t know where your data goes, you don’t control it.

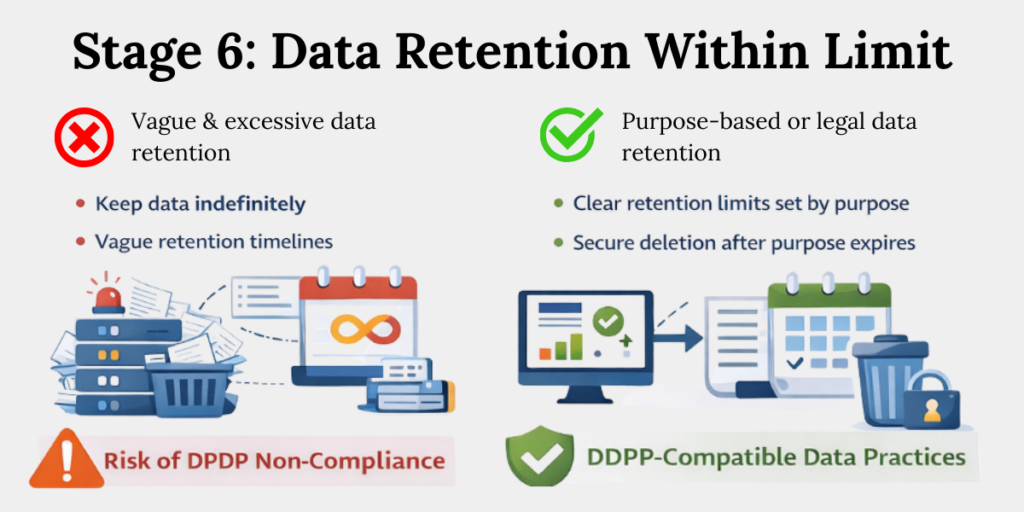

Stage 6: Retention Periods Must Be Actively Enforced

Section 8 of DPDP Act says personal data must be retained only as long as necessary for the stated purpose or legal obligation. Indefinite retention violates the DPDP Act and increases breach exposure.

Data hoarding is not caution.

It’s compliance debt.

Retention discipline requires:

- Define clear retention periods

Set clear timelines for how long each type of personal data will be kept. These timelines should be linked to the original purpose or legal requirement. If no clear reason exists, the data should not be retained. - Automate deletion where possible

Systems should be configured to delete or flag data once the retention period ends. Relying on manual deletion increases the chance of data being kept longer than allowed. Automation makes retention rules easier to follow. - Review retention regularly

Conduct periodic checks to confirm that data is not being stored beyond approved timelines. These reviews help catch old or forgotten datasets. Regular audits prevent retention from becoming a hidden risk.

Every extra day of unnecessary storage is a risk multiplier.

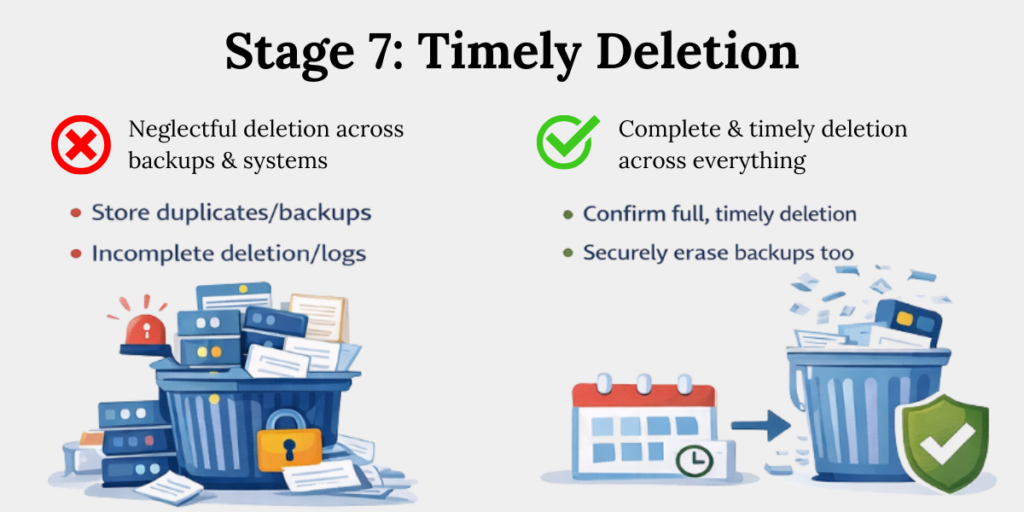

Stage 7: When to Delete Personal Data Under DPDP?

Upon purpose completion or consent withdrawal, personal data must be erased unless legally required otherwise. Organisations must ensure deletion across primary systems, backups, and vendor environments.

Deletion is the hardest stage to execute.

Mature deletion programs:

- Cover backups and archives

Deletion should not be limited to live systems. Personal data must also be removed from backups and archived storage where possible. Ignoring these areas often leads to incomplete deletion. - Include vendors and processors

Vendors holding personal data must also delete it when required. Organisations should clearly communicate deletion requests and confirm completion. If vendors are missed, deletion is not truly complete. - Keep proof of deletion

Maintain basic records showing when and how data was deleted. This helps demonstrate compliance during audits or complaints. Without evidence, deletion is hard to prove. - Respond to user requests quickly

Data Principals may request deletion of their personal data. Organisations should have a clear process to handle these requests without delay. Slow or unclear responses increase compliance risk.

If deletion is manual, it will eventually fail.

Conclusion

The DPDP Act does not reward good intentions

It rewards operational control.

Organisations that treat personal data as a living system – collected with intent, used with discipline, stored securely, and deleted on time – will scale safely.

Those that don’t will discover that data risk compounds silently, until it doesn’t.

Compliance is not paperwork.

It’s architecture.

Key Takeaways

- DPDP applies to personal data across its full lifecycle, not as a one-time compliance step.

- Personal data should be collected only for a clear purpose, and extra data increases risk.

- Consent must be clear, recorded, and easy to withdraw to stay compliant.

- Personal data can only be used for the purpose originally explained.

- Security safeguards must match the risk and sensitivity of the data

- Sharing data with vendors does not remove responsibility.

- Personal data must not be kept longer than needed.

- Data must be deleted once the purpose ends or consent is withdrawn.

- DPDP compliance works when data is managed as a system, not paperwork.