India’s Data Privacy Evolution

India did not wake up one morning and decide to regulate data privacy.

It was cornered into it – by digital scale, platform dependency, and the uncomfortable realisation that personal data had outgrown the law.

This blog traces how India’s data privacy framework evolved, from scattered protections to a statutory compliance regime under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, and what this evolution actually means for organisations today.

India’s Privacy Landscape: Early 2000s

Before 2023, India did not have a single data privacy law and relied on fragmented statutes and constitutional interpretation.

Privacy protections existed, but they were inconsistent, reactive, and centred on security rather than individual rights.

The Information Technology Act, 2000: Security Before Privacy

The Information Technology Act, 2000 focused on electronic records and cyber security, not on protecting personal data rights.

Its primary objective was to enable e-commerce and punish cybercrime, not to empower individuals.

In practice, privacy protection under the IT Act revolved around:

- Section 43A, which imposed compensation for failure to protect “sensitive personal data”

- Reasonable Security Practices, a vague standard often reduced to checkbox compliance

- IT Rules, 2011, which applied only to a narrow subset of “sensitive” data

This framework treated personal data like office Wi-Fi — available everywhere, secured loosely, and nobody quite responsible for it.

When Did Privacy Become a Fundamental Right in India?

According to the Supreme Court’s 2017 judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India, the right to privacy is a fundamental right under Constitution.

The Court confirmed that privacy is essential to life and personal liberty and applies to personal data, individual autonomy, and informational control.

This judgment fundamentally changed how personal data is legally protected in India and laid the foundation for modern data protection law.

Why the Puttaswamy Judgment Revolutionary?

Before Puttaswamy, privacy jurisprudence was inconsistent and uncertain. After it, privacy became enforceable, justiciable, and non-negotiable.

The Supreme Court made three key points:

- Privacy includes personal data, not just physical or private spaces

- Any limit on privacy must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate

- Personal data can only be collected for a clear and specific purpose

In simple terms, the State could no longer say, “Trust us, we’ll be careful.”

Why Constitutional Privacy Needed a Law?

Constitutional recognition of privacy was not sufficient because it could not regulate how personal data is processed at scale across digital systems.

While courts establish rights, only a practical law can define clear processing rules, assign accountability to organisations, and impose enforceable penalties – making privacy operational rather than theoretical.

As data volumes exploded across fintech, health tech, telecom, and government databases, India needed:

- Clear processing rules

- Defined accountability

- Enforceable penalties

Rights without operational law are inspirational. They are not implementable.

The Justice B.N. Srikrishna Committee: Designing India’s Privacy DNA

The Justice B.N. Srikrishna Committee provided India’s first comprehensive blueprint for a data protection law. The Committee drafted India’s first Personal Data Protection Bill. This report became the backbone of India’s modern privacy framework.

Nearly every core concept in the DPDP Act can be traced back to the Committee’s recommendations.

What the Committee Introduced?

The Committee formalised principles that now sound obvious – but weren’t at the time:

- Consent as the primary lawful basis for processing personal data

- Purpose limitation and data minimisation to restrict excessive data use

- Accountability of data handlers, not just data collectors

This was the moment India stopped borrowing privacy language and started designing its own framework.

Why the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 Failed?

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 failed because it was overly complex, imposed strict data localisation requirements, granted wide government exemptions, and created compliance obligations that many organisations were not ready to meet.

Due to these practical and policy concerns, the government withdrew the Bill in 2022 to redesign a more workable data protection framework.

What Exactly Went Wrong?

- Strict Data Localisation

The Bill required large volumes of personal data to be stored in India. This increased cost and complexity, especially for global and cloud-based businesses. - Broad Government Exemptions

The government retained wide powers to exempt itself from the law. This raised concerns about unchecked data use and weakened trust in the framework. - Heavy Compliance Burden

The Bill imposed detailed and prescriptive obligations on organisations. Many companies lacked the systems and maturity to meet these requirements. - Regulatory Over-Complexity

The framework introduced multiple classifications and layered obligations. This made compliance difficult to interpret and operationalise. - Misalignment with Digital Readiness

The Bill assumed a level of privacy maturity that did not exist across sectors. Small businesses and startups were particularly affected.

In 2022, the government withdrew the Bill entirely. That withdrawal was not a retreat – it was a recalibration. The outcome was a simpler, more executable privacy law designed for real-world compliance.

What Is the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023?

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 is India’s first enforceable law governing digital personal data that clearly defines individual rights and organisational responsibilities.

According to the DPDP Act, 2023, personal data may be processed only for lawful purposes and in accordance with clearly defined rights and obligations.

The Act grants Data Principals rights such as access, correction, erasure, and grievance redressal, while imposing mandatory Data Fiduciary duties including obtaining valid consent, limiting data use to lawful purposes, implementing security safeguards, reporting data breaches, and maintaining accountability.

Its framework focuses on making privacy rights operational through enforceable compliance obligations.

Scope and Applicability

The DPDP Act applies to:

- All digital personal data processed in India

- Certain processing outside India linked to Indian individuals

It excludes:

- Non-digitised offline records

- Personal or domestic use

This narrower scope is deliberate – India chose execution over ambition.

Difference Between PDP Bill 2019 and DPDP Act, 2023

| Aspect | PDP Bill, 2019 | DPDP Act, 2023 |

| Regulatory Approach | Highly prescriptive and complex | Simplified, compliance-first |

| Data Localisation | Broad and mandatory | No blanket localisation |

| Government Exemptions | Wide and unclear | Narrower, rule-based |

| Compliance Burden | Heavy, layered obligations | Outcome-oriented duties |

| Ecosystem Readiness | Misaligned with ground reality | Designed for executability |

| Status | Withdrawn in 2022 | Enacted and enforceable |

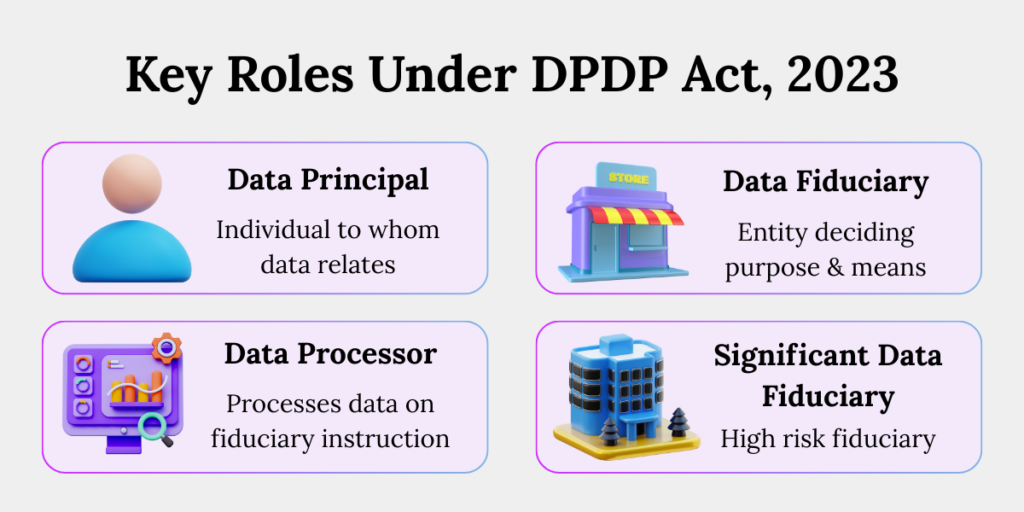

Key Roles Under the DPDP Act

The Act assigns responsibility by clearly defining who does what with personal data at every stage of processing. Each role has a specific legal function and corresponding obligations.

- Data Principal

The Data Principal is the individual to whom the personal data relates. They have enforceable rights over how their data is collected, used, corrected, erased, and how grievances are resolved. - Data Fiduciary

The Data Fiduciary is the organisation or entity that decides why and how personal data is processed. It is legally responsible for obtaining valid consent, ensuring lawful use, protecting data, and complying with all obligations under the Act. - Data Processor

The Data Processor processes personal data on behalf of a Data Fiduciary and only under its instructions. While it does not decide the purpose of processing, it must implement security safeguards and support the fiduciary’s compliance. - Significant Data Fiduciary (SDF)

A Significant Data Fiduciary is a notified Data Fiduciary that processes large volumes of data or sensitive information. SDFs must meet higher compliance standards, such as appointing a Data Protection Officer, conducting audits, and implementing enhanced risk management.

Accountability now has names — not excuses.

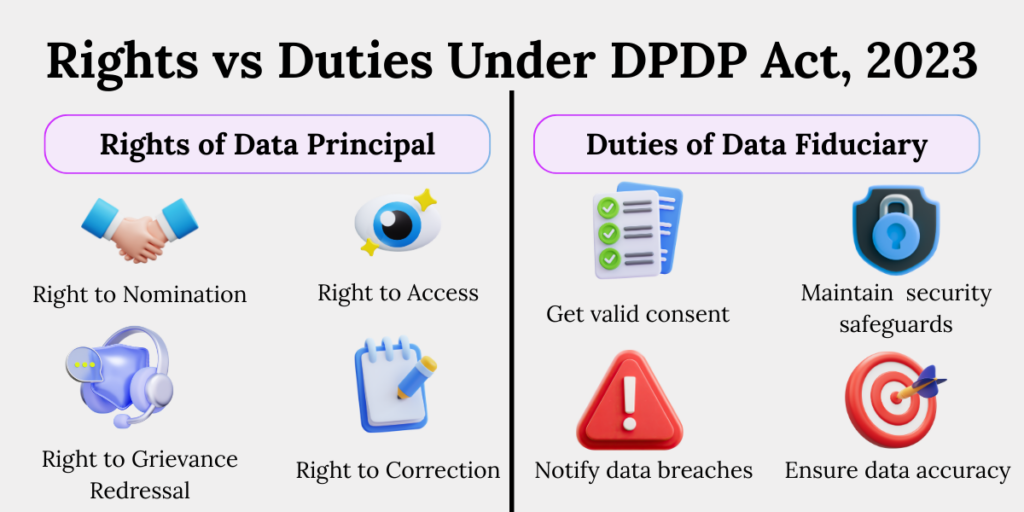

What Rights Does the DPDP Act Give Individuals?

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 grants individuals’ enforceable rights to understand, correct, and seek redress for how their personal data is processed.

These rights include access to information about data use, correction and erasure of inaccurate or unnecessary data, the ability to raise grievances with defined timelines, and the option to nominate another person to exercise rights in case of death or incapacity, focusing on practical transparency and accountability

In Practice, Individuals Can:

- Right to Access Information

Individuals can obtain confirmation of data processing, and a summary of how their personal data is being used. - Right to Correction and Erasure

Individuals can request correction of inaccurate data and deletion of data that is no longer necessary for a lawful purpose. - Right to Grievance Redressal

Individuals can raise complaints and must receive a response within prescribed timelines. - Right to Nominate

Individuals can nominate another person to exercise their rights in case of death or incapacity.

The Act protects dignity – without turning compliance into a philosophical exercise.

Obligations of Businesses Under the DPDP Act

Under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, Data Fiduciaries must process personal data lawfully by obtaining valid consent, limiting use to defined purposes, implementing security safeguards, ensuring accuracy, reporting data breaches, and maintaining grievance redressal mechanisms – making accountability a legal obligation.

Core Compliance Duties Include:

- Obtain Valid Consent

Data Fiduciaries must collect personal data only after obtaining consent that is free, informed, specific, and capable of being withdrawn at any time. Consent must be linked to a lawful purpose and cannot be bundled, forced, or implied. - Implement Security Safeguards

Data Fiduciaries must put in place appropriate technical and organisational measures to protect personal data. This includes controls such as access management, encryption, monitoring, and internal security policies. - Notify Personal Data Breaches

Data Fiduciaries must notify the Data Protection Board of India and affected individuals in the event of a personal data breach. The notification must be timely and contain sufficient information to enable risk assessment and mitigation. - Ensure Data Accuracy

Data Fiduciaries must take reasonable steps to ensure personal data is accurate and up to date when it is used to make decisions about individuals. Inaccurate or outdated data must be corrected or erased to prevent harm.

Compliance is no longer about drafting policies. It is about building systems that work at scale.

How Does DPDP Act Regulate Cross Border Transfer?

Under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, cross-border transfer of personal data is permitted by default and regulated through a government-controlled allow-list mechanism.

Data Fiduciaries may transfer personal data outside India unless the Central Government expressly restricts transfers to specific countries or entities, and such transfers must comply with notified conditions, marking a shift from strict data localisation to a risk-based, responsible data transfer framework.

There is no default data localisation requirement.

India adopts a government-controlled allow-list approach to cross-border data transfers.

Transfers are:

- Allowed unless expressly restricted

- Subject to conditions notified by the Central Government

India moved from “keep data here” to “move data responsibly.”

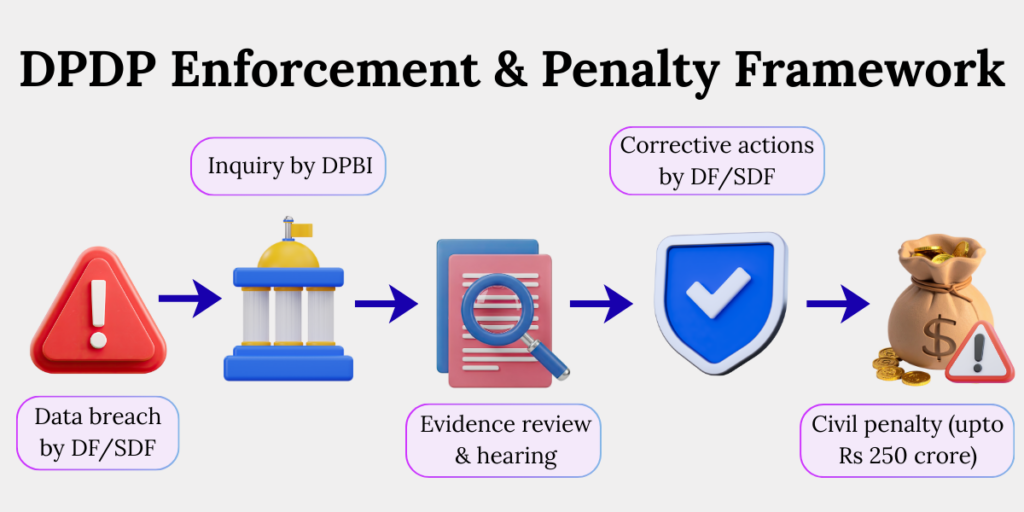

What is the Data Protection Board of India?

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 is enforced by the Data Protection Board of India, which functions as an independent adjudicatory authority.

The Board is responsible for inquiring into non-compliance, directing remedial measures, and issuing penalty orders against Data Fiduciaries and Significant Data Fiduciaries, making it the central enforcement body for India’s data protection regime.

Powers of DPBI

- Initiation of Inquiries

The Board can initiate inquiries into personal data breaches, compliance failures, and violations of Data Principal rights. These inquiries may arise from complaints, breach notifications, or suo motu action. - Evaluation of Evidence

The Board examines documents, technical records, and other evidence submitted during proceedings. This helps determine whether obligations under the DPDP Act have been breached. - Hearing and Representation

The Board allows affected organisations and individuals to present their explanations and responses. This ensures decisions are made after considering all relevant facts. - Issuance of Directions and Remedies

The Board may issue binding directions requiring corrective actions in addition to penalties. These directions can mandate changes to internal processes, security safeguards, or grievance systems.

Penalties Under the DPDP Act

According to the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, monetary penalties for non-compliance can extend up to ₹250 crore per instance.

While determining penalties, the Data Protection Board considers factors such as the nature and seriousness of the breach, its duration and repetition, and the mitigation steps taken by the organisation, reflecting an enforcement model that is corrective and compliance-focused rather than punitive.

Penalty Framework

- Nature of Penalties

Penalties under the DPDP Act are civil in nature and do not involve criminal prosecution. The focus is on correcting non-compliance rather than imposing criminal liability. - Maximum Penalty Limits

The Act prescribes monetary penalties that can go up to ₹250 crore per violation. The applicable amount depends on the specific obligation breached. - Penalty Assessment Criteria

The Board assesses penalties based on the seriousness of the violation and the harm caused to Data Principals. It also considers the duration, frequency, and recurrence of non-compliance. - Impact of Mitigation Efforts

Timely breach reporting, corrective action, and cooperation with the Board can reduce penalty exposure. Demonstrating accountability and compliance intent is a key mitigating factor.

What Do the DPDP Rules, 2025 Actually Add?

The Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025 operationalise the DPDP Act by translating legal principles into specific, enforceable compliance requirements.

The Rules define how consent notices must be issued, prescribe timelines and formats for personal data breach reporting, set safeguards for processing children’s data, and establish detailed grievance redressal mechanisms, turning statutory obligations into day-to-day operational actions for organisations.

This is where compliance becomes real.

The DPDP Rules, 2025 convert statutory principles into operational instructions.

Think of the Act as architecture. The Rules are plumbing and wiring.

Difference between DPDP Act

| Aspect | DPDP Act, 2023 | DPDP Rules, 2025 |

| Purpose | Establishes legal framework | Operationalises the framework |

| Nature | Principle-based statute | Procedural and executable |

| Focus | Rights, duties, penalties | Notices, timelines, formats |

| Consent | Defines validity requirements | Prescribes notice mechanics |

| Breach Handling | Mandates notification | Specifies reporting process |

Limitations of the DPDP Act

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 adopts a pragmatic, compliance-first approach, but this design comes with clear limitations.

The Act applies only to digital personal data, does not provide rights such as data portability or objection to processing, allows broad government exemptions, offers limited institutional independence for the regulator, and leaves certain compliance requirements open to interpretation, especially for small and medium enterprises, reflecting India’s choice to prioritise governability and enforcement feasibility over a maximalist rights framework.

Key Limitations Include:

- Digital-only scope

The DPDP Act applies only to personal data processed in digital form or data that is later digitised. Personal data held purely in physical records remains outside the law’s scope. - No data portability or objection rights

The Act does not grant individuals the right to transfer their data between service providers or object to certain processing activities. This limits individual control compared to broader global data protection frameworks. - Broad government exemptions

The Central Government can exempt certain data processing activities from the Act in specified situations. These exemptions raise concerns around proportionality and oversight. - Limited regulator independence

The Data Protection Board operates under executive control for appointments and functioning. This may affect perceptions of regulatory independence and impartial enforcement. - Compliance ambiguity for SMEs

Several obligations are principle-based and rely on future guidance or interpretation. Small and medium enterprises may struggle with clarity on implementation expectations.

India chose governability over maximalism. Whether that balance holds will depend on enforcement.

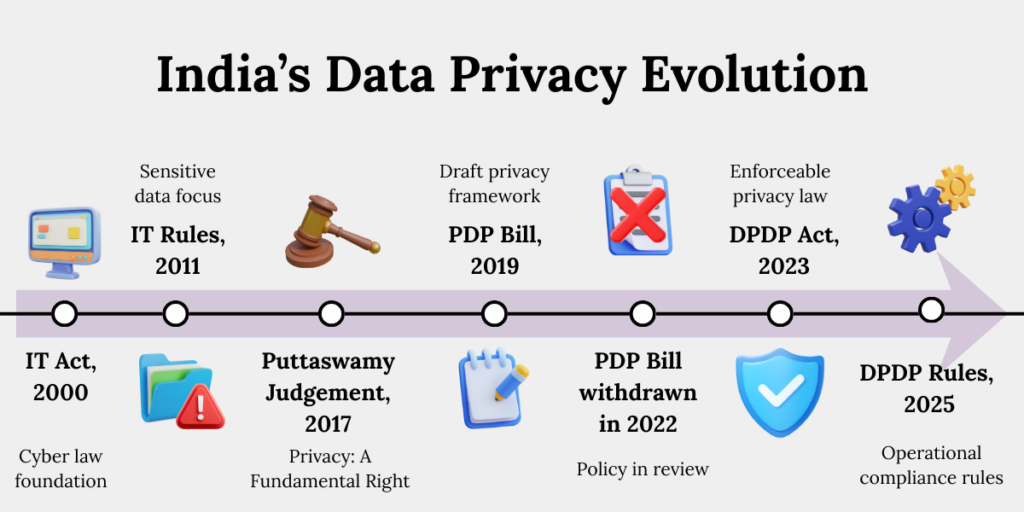

India’s Data Privacy Evolution: A Snapshot

| Year | Milestone |

| 2000 | IT Act enacted |

| 2017 | Privacy recognised as a Fundamental Right |

| 2019 | PDP Bill introduced |

| 2022 | PDP Bill withdrawn |

| 2023 | DPDP Act enacted |

| 2025 | DPDP Rules enforced |

Conclusion

India’s data privacy regime has evolved from fragmented protections to an enforceable compliance framework under the DPDP Act, 2023. With defined rights, duties, penalties, and operational rules, data protection in India is now a legal and operational mandate.

Key Takeaways

- India initially relied on fragmented laws like the IT Act, 2000, which focused on cyber security rather than personal data rights.

- In 2017, the Puttaswamy judgment recognised privacy as a Fundamental Right covering personal data.

- Constitutional protection alone could not regulate large-scale digital data processing, requiring legislation.

- In 2023, India adopted a practical, enforceable data protection law, Digital Personal Data Protection Act, defining rights of individuals and duties of organisations.

- The Data Protection Board of India enforces compliance under the DPDP Act, supported by DPDP Rules, 2025, with penalties up to ₹250 crore.