Sensitive Data Types Explained

Sensitive data is not just “important data.”

It is high-risk data – the kind that can financially, physically, or socially (and irreversibly) harm an individual if exposed, misused or mishandled.

That distinction is where most organisations slip. They protect all data equally and assume that’s enough. It isn’t.

This blog breaks down sensitive data types, explains why regulators treat them differently, and gives you a practical blueprint for handling them without panic, overengineering or blind fear.

What Is Sensitive Data?

Sensitive data refers to specific categories of personal data that, if compromised, can cause significant harm to an individual – financial loss, discrimination, identity theft, or physical risk

Because the consequences are higher, regulators impose stricter safeguards, tighter access controls, and enhanced accountability for its handling.

In practice, sensitive data is not defined by how valuable it is to a business, but by how damaging it can be to a person.

If personal data is your office building, sensitive data is the server room with the “authorised access only” sign.

Why Are Some Data Types Classified as “Sensitive”?

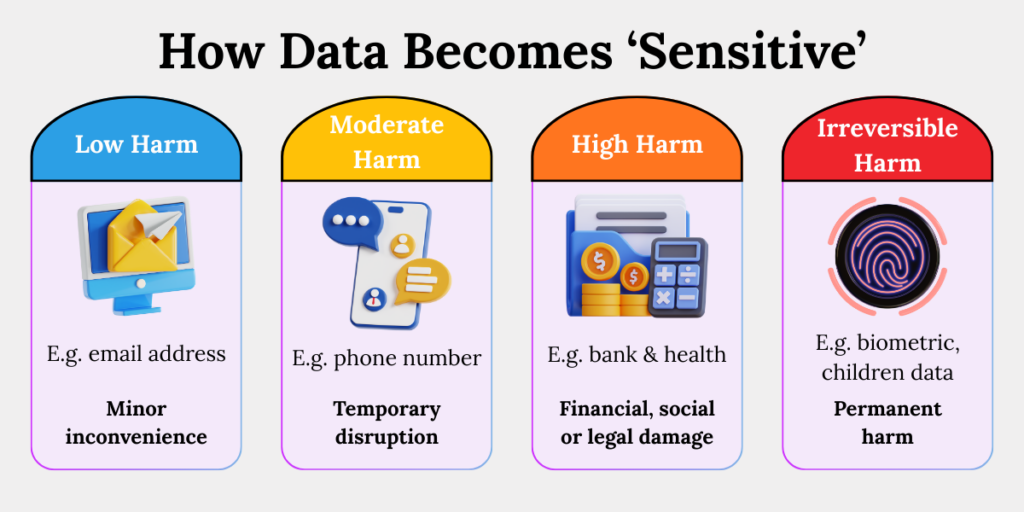

Sensitivity is about impact, not volume. If misuse of data can materially harm a person’s rights, safety, or dignity, regulators escalate protections.

Think of data protection as architecture. Not every wall needs a bunker. But some rooms store explosives.

A leaked email address is inconvenient.

But a leaked fingerprint or Aadhaar number is catastrophic.

Regulators design stricter obligations around sensitive data because:

- The damage is harder, or impossible, to reverse

- The data enables cascading misuse across systems

- Individuals have limited ability to protect themselves post-breach

Regulatory logic is simple: Higher risk → higher duty of care → stricter safeguards.

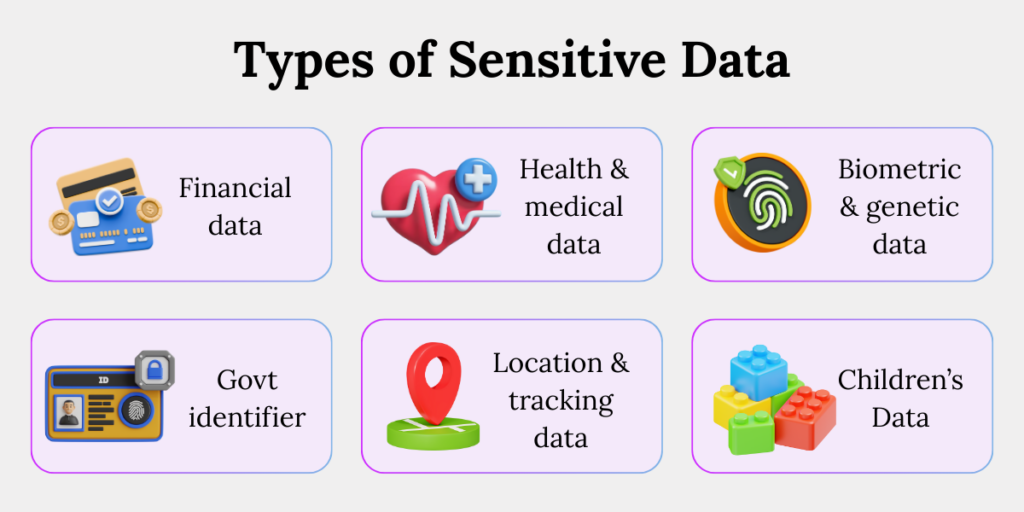

Core Categories of Sensitive Data

1. Financial Information

Financial data enables direct monetary harm if exposed. This includes bank account numbers, card details, UPI IDs, credit histories, and transaction records.

In practice, financial data is sensitive because:

- It enables immediate fraud

Bank account numbers, card details, UPI IDs, and transaction metadata allow attackers to move money instantly. Fraud does not require full credentials – partial data and behavioural patterns are often sufficient. - Losses are often irreversible

Once funds are transferred, recovery depends on banking timelines, dispute mechanisms, and proof thresholds. Many victims never recover the full amounts. - Victims bear the burden of proof

Customers must prove fraud, innocence, and negligence – while attackers remain anonymous. The asymmetry is severe.

If it can empty a wallet before a customer support ticket is raised, it’s not ‘just data.’

How this fails in practice:

A shared spreadsheet with masked card numbers still exposes enough metadata for social engineering. Fraud doesn’t need full numbers – patterns are enough.

Architectural rule:

Treat financial data like cash, not paperwork. Encrypt it. Restrict access. Log every touchpoint.

2. Health and Medical Data

Health data exposes deeply personal information that can lead to discrimination or stigma. This includes medical records, diagnoses, prescriptions, mental health data, and insurance claims.

Health data is uniquely sensitive because:

- It reveals vulnerabilities

Medical histories, diagnoses, prescriptions, and mental health data expose conditions individuals may never disclose publicly. - Enables discrimination

Health data can influence hiring decisions, insurance premiums, creditworthiness, and social treatment – often invisibly - Cannot be meaningfully anonymised

Even pseudonymised health datasets can often be re-identified when combined with other data points.

How this fails in practice:

Health data leaks through dashboards, third-party tools, or test environments, not core medical systems.

Architectural rule:

Treat this like a sealed medical file. Store it separately, limit who can see it, and erase it when the treatment ends.

3. Biometric and Genetic Data

Biometric data is permanent & uniquely identifying. Once leaked, it’s lost forever. This includes fingerprints, facial scans, iris data, voiceprints, and DNA information.

That permanence makes biometrics one of the highest-risk data types globally.

Passwords can be changed. Faces cannot.

Biometric & genetic data is uniquely sensitive because:

- Cannot be changed

Fingerprints, facial scans, iris data, voiceprints, and DNA are lifelong identifiers. A compromised biometric is compromised forever. - Enables impersonation at scale

Biometrics are increasingly used for authentication. Once leaked, attackers can bypass multiple systems. - Centralised failure risk

Biometric databases create high-value targets. A single breach impacts thousands simultaneously.

How this fails in practice:

Centralised storage, weak key management, and poor access logging create silent, systemic exposure.

Architectural rule:

Store biometrics only when necessity is unquestionable. Isolate systems. Avoid centralised repositories unless absolutely necessary.

4. Government Identifiers

Government-issued identifiers enable identity takeover at scale. They act as universal identity keys. Examples include Aadhaar numbers, passport numbers, voter IDs, and driving licence details.

These identifiers are sensitive because:

- Unlocks multiple systems

One identifier can enable access to banking, telecom, travel, taxation, and government services. - Hard to revoke or replace

Replacing a government ID is slow, bureaucratic, and often incomplete. - Enables synthetic identity fraud

Fraudsters combine identifiers with leaked data to create believable fake identities.

How this fails in practice:

IDs are collected for convenience, stored indefinitely, and accessed by teams without necessity.

Architectural rule:

Collect only when legally required, lock them away from general systems, and never reuse them across workflows.

5. Location and Tracking Data

Location data reveals behaviour patterns and physical movements. This includes GPS data, real-time tracking, IP-based location history, cross-app behavioural tracking and travel logs.

Location data is sensitive because:

- Reveals daily routines

Home addresses, workplaces, religious visits, medical appointments, and habits can all be inferred - Enables physical risk

Precise or continuous tracking can expose individuals to stalking, harassment, or targeted harm. - Becomes sensitive over time

Even low-precision data becomes highly revealing when accumulated.

How this fails in practice:

Tracking is enabled by default, logged endlessly, and reviewed by teams who never needed access.

Architectural rule:

Treat persistent location tracking as sensitive by default – even if the law is silent. Regulators usually do.

6. Children’s Data

Children’s data is sensitive because minors cannot fully assess risk or consent meaningfully. This includes any personal data relating to individuals below the legally defined age threshold.

Children’s data are sensitive because:

- Meaningful consent is limited

Children cannot fully understand long-term data consequences. - Higher exploitation risk

Children’s data is frequently targeted for profiling, manipulation, or grooming. - Stronger regulatory expectations

Regulators impose stricter standards regardless of organisational intent.

How this fails in practice:

Platforms assume users are adults unless told otherwise. Regulators assume the opposite.

Architectural rule:

Treat children’s data like a protected zone. Collect less, guard more, and design for higher protection by default.

Because “We didn’t know users were minors” is not a defensible position.

Sensitive vs Personal Data

All sensitive data is personal data. Not all personal data is sensitive.

Sensitive data is a high-risk subset of personal data that requires enhanced safeguards due to the severity of harm its misuse can cause.

While all sensitive data qualifies as personal data, only specific categories – such as financial, biometric, health, children, and government identifiers – trigger elevated compliance, security, and accountability obligations.

Technical & Practical Difference

| Factor | Personal Data | Sensitive Data |

| Risk Profile | Moderate | High to critical |

| Harm Severity | Usually reversible | Often irreversible |

| Access Model | Role-based | Strict, minimal, logged |

| Encryption | Recommended | Mandatory |

| Retention Logic | Business-driven | Purpose-bound, short |

| Breach Impact | Inconvenience | Financial, legal, physical |

| Oversight | Standard | Heightened |

| Examples | Email, name | Biometrics, Aadhaar, health |

This distinction matters because controls, audits, and approvals must scale with sensitivity, not convenience.

How Sensitive Data Fails in Practice

Sensitive data rarely fails because of hackers alone. It fails because of routine organisational behaviour. Sensitive data failures are slow governance leaks.

Common failure patterns we observe:

- Over-collection “just in case”

Teams collect sensitive fields without necessity, expanding exposure without operational benefit. What starts as convenience quietly becomes liability. - Shared access across teams

Sensitive data spreads across departments through dashboards, exports, and internal tools. Each additional viewer multiplies risk. - Vendor sprawl without audits

Third-party tools access sensitive data without audits, contracts, or deletion guarantees. Responsibility becomes fragmented. - No deletion logic after purpose expiry

Sensitive data persists long after purpose expiry. Silent retention is one of the most common audit failures.

These are governance failures, not technical ones.

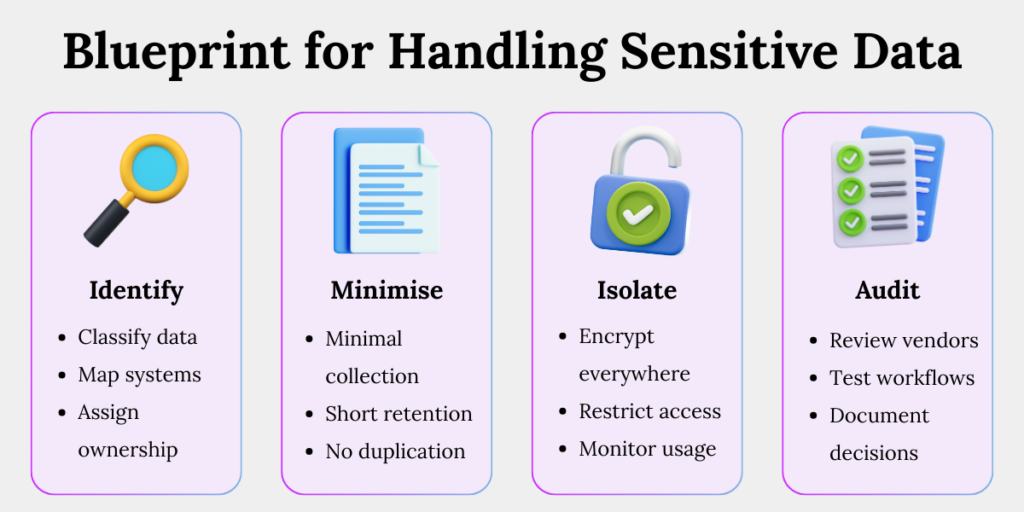

A Practical Blueprint for Handling Sensitive Data

If you remember nothing else, remember this structure.

1. Identify Precisely

- Classify rigorously: Separate sensitive data from general personal data.

- Map systems: Document where sensitive data lives and flows.

- Assign ownership: Every sensitive dataset needs a responsible owner.

2. Minimise Aggressively

- Collect narrowly: Justify every sensitive field.

- Shorten retention: Delete as soon as purpose ends.

- Avoid duplication: Backups and exports often become blind spots.

3. Isolate Technically

- Encrypt everywhere: At rest and in transit.

- Restrict access: Only roles that genuinely need it.

- Monitor usage: Log and review privileged access

4.Audit Relentlessly

- Review vendors: Contracts, controls, and sub-processors.

- Test workflows: Deletion, consent withdrawal, breach response.

- Document decisions: Regulators audit reasoning, not intentions.

This is how a data fortress stays standing.

Conclusion: Sensitivity Is a Design Choice

Sensitive data doesn’t become dangerous by accident.

It becomes dangerous when organisations design systems without acknowledging risk.

Compliance isn’t about collecting less data forever. It’s about knowing which rooms need reinforced walls.

Build your data architecture accordingly – and you won’t need to panic when regulators come knocking.

Key Takeaways

- Sensitive data is defined by harm, not importance, and requires stronger safeguards than general personal data.

- Regulators classify data as sensitive based on impact, focusing on irreversibility, misuse potential, and loss of individual control.

- Financial data is sensitive because fraud is immediate, recovery is uncertain, and victims must prove innocence.

- Health, biometric, government ID, location, and children’s data are sensitive due to permanence, profiling risk, and power imbalance.

- Sensitive data failures stem from governance gaps, such as over-collection, shared access, unchecked vendors, and no deletion logic.

- Treating all data equally is a design flaw, not a compliance strategy.

- Effective sensitive data protection starts with classification, minimisation, isolation, and continuous audits.

- Compliance succeeds when sensitivity is engineered into systems, not patched through policies.