DPDP Rule 15 Explained: Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Data

India’s Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) framework fundamentally changes how organisations collect, use, and move personal data — including where that data is allowed to go.

So, is cross-border data transfer still a safe assumption for your organisation?

Cross-border data transfers are no longer an invisible technical choice made by IT teams.

Under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 and the DPDP Rules, 2025, they are a regulated compliance function. Rule 15 governs how, when, and under what conditions personal data can move outside India — and places decisive control in the hands of the Central Government.

This blog breaks down Rule 15, explains what it allows, what it restricts, and what Data Fiduciaries must prepare for immediately.

Statutory Basis: Where Rule 15 Comes From

Rule 15 of the DPDP Rules, 2025 is issued under Section 16 of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023.

Section 16 provides the legal authority for cross-border data transfers and empowers the Central Government to regulate them.

Together, they establish India’s official position on international data movement — permitted by law but governed by executive control.

The Act defines the “what,” and the Rules explain the “how.

Rule 15: Cross-Border Transfer Rules

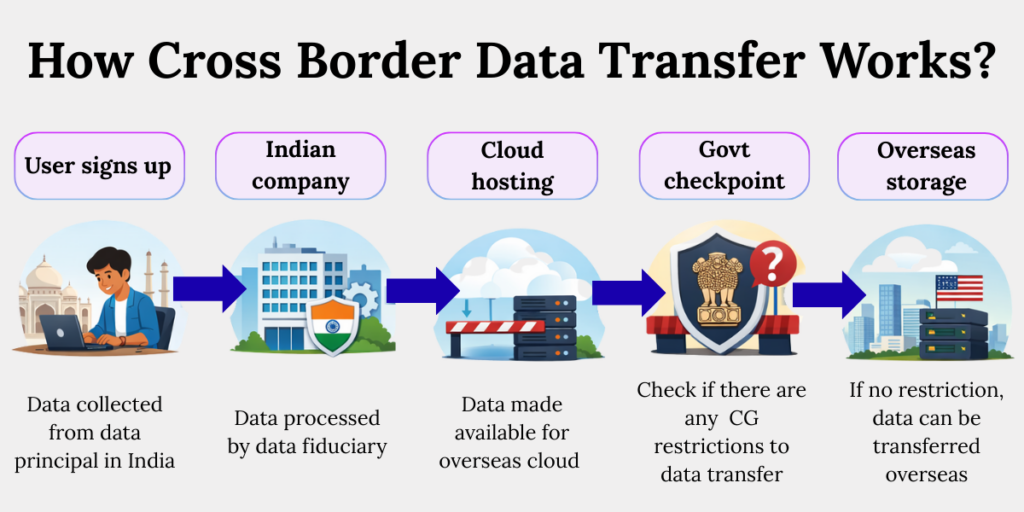

Rule 15 permits a Data Fiduciary to transfer personal data outside the territory of India, subject to:

- Requirements specified by the Central Government

The Central Government can set conditions for when and how personal data may be transferred outside India. These conditions can differ based on the sector, type of data, or destination country.

- Issued through general or special orders

The Government may issue orders that apply to everyone or orders that apply only to specific countries, entities, or situations. Once issued, these orders are legally binding.

- Applicable to foreign States and their controlled entities

Restrictions apply not only to foreign governments but also to companies or organisations controlled by them. This prevents indirect access to Indian personal data through private entities.

In simple terms:

Cross-border transfer is allowed — but only as long as the Government has not restricted it.

Cross-border transfers are allowed — until the Government says, “Not this way.”

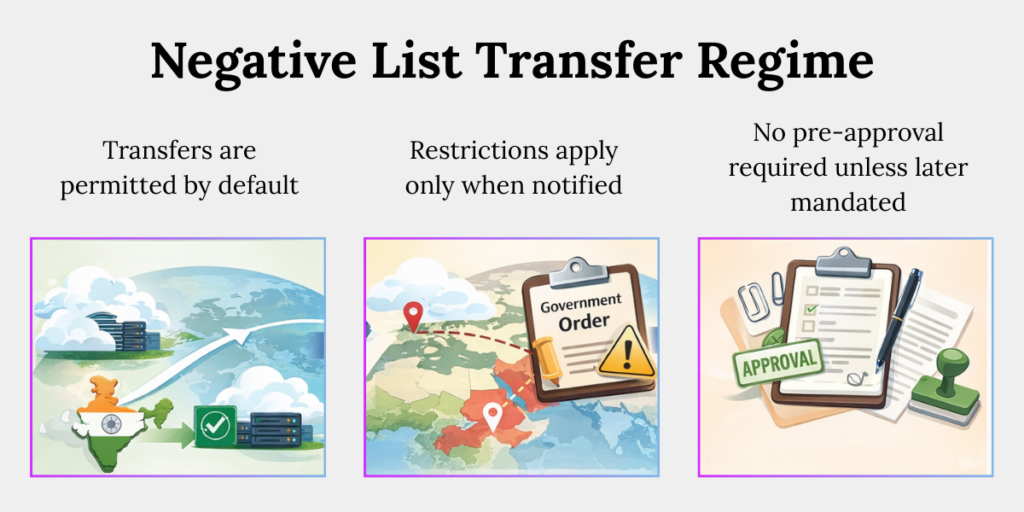

A Negative-List Transfer Regime

Unlike many global privacy regimes, India adopts a negative-list approach — cross-border data transfers are allowed by default and restricted only when the Government says otherwise.

This means:

- Transfers are permitted by default

Organisations do not need prior approval to transfer data outside India unless restricted by law.

For example, a company using a global cloud server can continue hosting Indian user data overseas unless the Government restricts that destination. The data can travel — until the rulebook changes the destination.

- Restrictions apply only when notified

Obligations arise only after the Government issues a formal order specifying restrictions or conditions.

For instance, if a country is added to a restricted list, only then must organisations stop or modify transfers to that location. No notification, no restriction — but always stay alert.

- No pre-approval is required unless mandated later

Businesses do not need advance clearance to move data abroad today, but this can change through future orders.

For example, a SaaS company can continue serving global clients unless a new rule introduces approval requirements. No permission slips today — but keep the pen ready. This model offers flexibility, but organisations must stay alert because new government orders can quickly change what is allowed, and what isn’t.

What Rule 15 Does Not Mandate (Yet)

Many data protection frameworks tightly control cross-border data transfers through fixed legal mechanisms.

India’s DPDP framework takes a more flexible approach.

Instead of embedding fixed transfer mechanisms into the Rules, Rule 15 leaves room for the Central Government to introduce conditions over time, based on policy, security, and sectoral considerations.

Rule 15 does not require:

- Adequacy determinations

There is currently no official list of approved or restricted countries for cross-border transfers.

Personal data may be transferred outside India unless the Government later restricts specific destinations through a formal order.

- Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs)

Rule 15 does not prescribe mandatory contractual clauses that must be used when transferring data abroad.

Organisations are free to structure transfer agreements, subject to future conditions that may be introduced.

- Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs)

Intra-group data transfers do not require prior regulatory approval under the DPDP Rules.

Multinational groups can continue internal transfers unless restricted by future notifications.

- Transfer Impact Assessments (TIAs)

Organisations are not legally required to assess foreign government access or surveillance risks before transferring data.

Such assessments may become relevant later, but they are not mandatory today.

- Mandatory localisation for all data

The DPDP Rules does not impose blanket data localisation. Personal data is not required to remain within India unless a specific restriction applies.

Rule 15 is intentionally flexible, allowing transfer rules to change as risks and policy priorities evolve. Organisations can operate freely — but only if they stay alert to new restrictions.

Central Government Powers

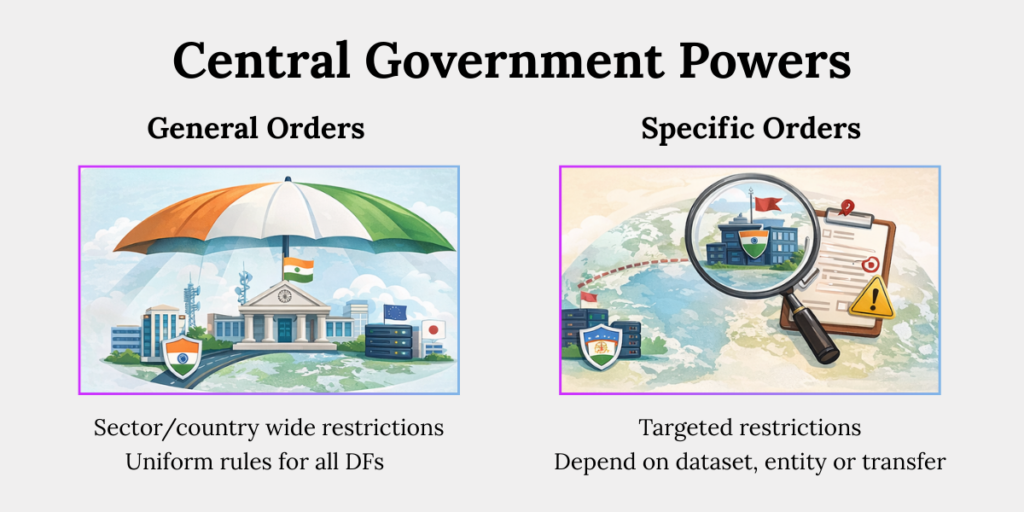

General and Special Orders

The Central Government may issue:

- General orders

General orders apply widely and uniformly. They are used when the Government wants to regulate cross-border data transfers across an entire sector, country, or category of personal data.

These orders usually apply:

- When a broad risk is identified

- When uniform rules are needed for consistency and clarity

- To all Data Fiduciaries or a defined class of organisations

Example:

A general order may restrict transfers of certain financial data to a specific country across all companies.

Special orders

Special orders are targeted and specific. They apply only to identified entities, transfers, or situations where a focused risk is identified.

These orders usually apply:

- When the risk is limited or case-specific

- To specific Data Fiduciaries, processors, or datasets

- When broader restrictions are unnecessary

Example:

A special order may restrict one company from transferring data to a particular foreign service provider.

These orders may:

- Prohibit transfers to specified countries

The Government may completely ban transfers of personal data to certain countries. Once prohibited, organisations must stop sending data to those destinations immediately.

This is typically used when a country poses national security, legal, or strategic risks. - Restrict transfers to certain foreign entities

Even if a country is not restricted, the Government may block transfers to specific entities within that country. This prevents indirect access to Indian personal data through high-risk organisations.

Restrictions may apply to companies controlled by foreign governments or those linked to sensitive activities. - Impose mandatory conditions before transfer

Instead of banning transfers, the Government may allow them only if certain safeguards are met. Organisations must comply with these conditions before continuing transfers.

These conditions may include security controls, data storage requirements, or access limitations.

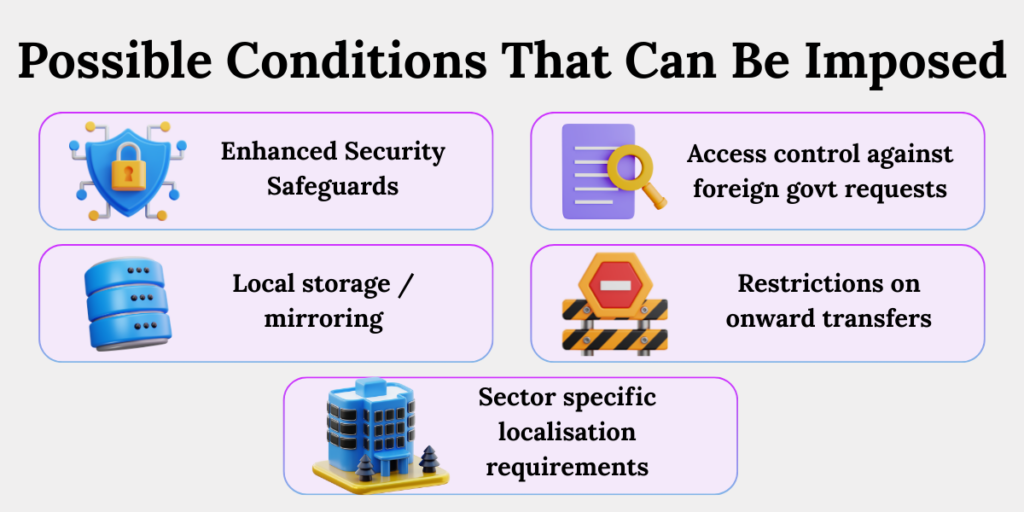

Possible Conditions the Government May Impose

Rule 15 gives the Central Government broad discretion to impose transfer conditions through general or special orders, which may apply to all Data Fiduciaries at any time.

The government orders may require:

- Enhanced security safeguards

Organisations may be required to strengthen how personal data is protected before it is transferred outside India.

This can include stronger encryption, tighter access controls, and hardened systems to reduce the risk of unauthorised access. - Access controls against foreign government requests

Data Fiduciaries may need measures to limit, monitor, or record access requests from foreign governments.

This ensures visibility and accountability when personal data is processed outside India. - Local storage or mirroring

Certain datasets may be required to be stored or copied within India, even if processing happens abroad. This helps ensure regulatory access and continuity in case overseas access is restricted. - Restrictions on onward transfers

Personal data transferred outside India may not be allowed to move freely to other entities or countries.

Further sharing may be restricted or allowed only under additional safeguards. - Sector-specific localisation requirements

Sensitive or high-risk sectors may face tighter transfer and storage controls. These restrictions are likely to be targeted rather than applied uniformly across all industries.

These conditions can be introduced through government orders without changing the Act or the Rules.

Interaction with Significant Data Fiduciaries (SDFs)

Higher Scrutiny for SDFs

For Significant Data Fiduciaries, cross-border transfers attract enhanced oversight. This is because SDFs process large volumes of personal data, sensitive data, or data that poses higher systemic or strategic risk.

The Central Government may notify:

- Specific categories of personal data

Certain datasets may be identified as critical or sensitive and prohibited from being transferred outside India altogether. - Associated traffic or metadata

Restrictions may also extend to related technical data such as logs, usage data, and metadata generated during processing. This prevents indirect exposure of sensitive information.

Such data must not be transferred outside India, regardless of consent or business necessity.

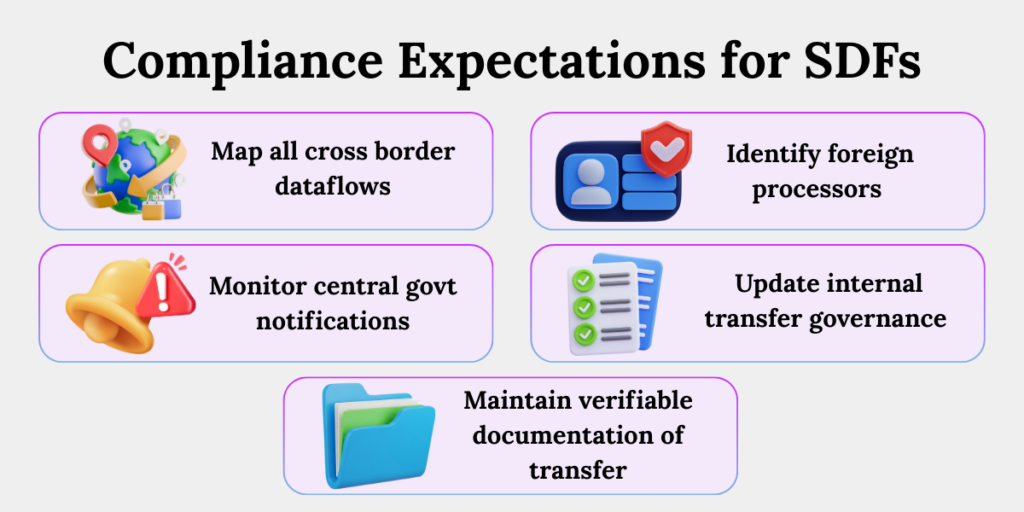

Operational Impact on SDFs

SDFs must:

- Conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments

Cross-border transfers must be evaluated for systemic, strategic, and national-level risks before implementation. - Implement risk-based transfer governance

Decisions around data transfers must be reasoned, documented, and capable of withstanding regulatory scrutiny. - Prepare for government-mandated localisation

Systems, vendors, and architectures must be capable of operating even if offshore processing or storage is restricted.

For SDFs, Rule 15 directly influences technology architecture, vendor selection, and long-term data strategy.

Relationship with Sectoral and Localisation Laws

Now a question may arise, “Does Rule 15 override every other data law your organisation follows?”

The answer: It does not.

Sector-specific and localisation requirements continue to apply alongside Rule 15.

For example, financial data may still need to remain in India under RBI norms, telecom operators must comply with telecom-specific data retention rules, and market and insurance entities remain subject to SEBI and IRDAI regulations.

Rule 15 operates in addition to these obligations, not in place of them.

Compliance must be assessed across all applicable laws.

When multiple laws apply, the strictest requirement always prevails.

In data compliance, the toughest rule wins — every time.

Compliance Obligations for Data Fiduciaries

Even without detailed transfer rules today, Data Fiduciaries must act proactively.

Mandatory readiness actions include:

- Map all cross-border data flows

Organisations must clearly track which personal data moves outside India and for what purpose.

This includes identifying destination countries, systems, and business functions involved in the transfer. - Identify foreign processors and sub-processors

It is important to know which overseas vendors, cloud providers, or partners can access personal data.

Organisations should also understand the legal authority under which these entities operate. - Monitor Central Government notifications

Transfer conditions can change through government orders at any time. Regular monitoring ensures organisations can respond quickly when new restrictions are introduced. - Update internal transfer governance frameworks

Internal policies and procedures must reflect how Rule 15 operates in practice. This helps teams make consistent and compliant decisions on cross-border transfers. - Maintain verifiable documentation of transfers

Every cross-border transfer should be supported by clear records explaining why the transfer is allowed.

This documentation is essential during audits or regulatory reviews.

Preparation today reduces disruption tomorrow.

Implementation Timeline

So, when does Rule 15 come into effect?

Rule 15 becomes enforceable 18 months after notification.

This period allows organisations to:

- Re-architect global data flows

- Update cloud and vendor contracts

- Strengthen governance controls

Once the transition period ends, enforcement will follow.

Why Rule 15 Matters Strategically

Rule 15 allows organisations to move personal data across borders without rigid upfront barriers. At the same time, it ensures the Central Government retains control over where and how data can be transferred.

This balance supports global business operations while protecting national and strategic interests.

For organisations, it means flexibility today — and the need for readiness tomorrow.

Conclusion

Rule 15 is not about permission — it is about preparedness.

Organisations that treatcross-border data transfers as a governance function will adapt smoothly. Those that delay will face disruption when restrictions arrive.

Data may cross borders. Compliance cannot lag behind.

Key Takeaways

- Cross-border transfers are permitted by default

- Central Government controls the exceptions

- Restrictions may be country, entity, or data-specific

- SDFs face stricter localisation risks

- Sectoral laws continue to apply

- 18-month transition period is critical