DPDP Rule 13: What Significant Data Fiduciaries Must Comply With

The Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 is India’s primary law governing how personal data is collected, used, and protected. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all law.

It is a risk-based framework that scales obligations based on how much personal data you handle, how sensitive it is, and how much harm misuse can cause.

At its core, the Act establishes baseline responsibilities for all organisations that decide why and how personal data is processed.

But it also recognises a critical reality: some entities exercise far greater control over personal data—and therefore pose greater risk.

This is why the DPDP Act introduces the concept of Significant Data Fiduciaries.

Who Is a Data Fiduciary?

A Data Fiduciary is any person or entity that determines the purpose and means of processing personal data.

In practical terms:

- If you collect personal data

- Decide how it will be used

- And control the systems that process it

—you are a Data Fiduciary under the DPDP Act.

Core responsibilities of Data Fiduciaries include:

- Issuing clear, itemised privacy notices

- Collecting valid, informed consent

- Implementing reasonable security safeguards

- Enabling Data Principal rights

- Reporting personal data breaches

- Establishing effective grievance redressal mechanisms

These obligations apply to every Data Fiduciary, regardless of size or sector.

But the DPDP framework does not stop at baseline duties.

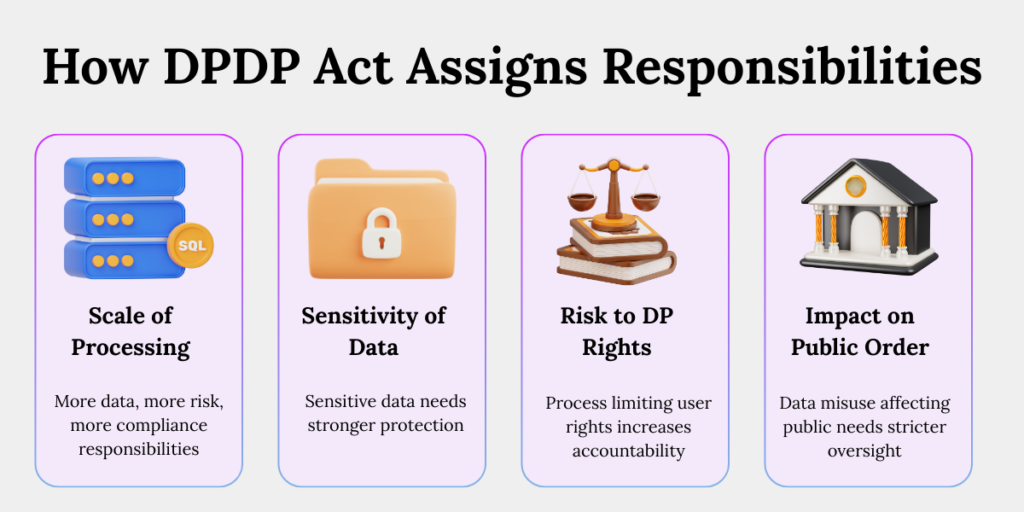

How DPDP Act Assigns Responsibilities

The DPDP Act deliberately avoids treating all Data Fiduciaries alike.

Why? Because:

- A small service processing limited contact data, and

- A large platform processing behavioural, financial, or sensitive personal data

do not present the same risk to individuals or society.

The Act therefore embeds differentiated accountability, based on:

1. Scale of processing

It looks at how much personal data is collected, used, or stored and how many individuals are affected by that processing. Processing data of a few thousand users does not carry the same risk as processing data of millions.

2. Sensitivity of data

This is the nature of the personal data involved. Data that reveals financial details, health information, location, or behavioural patterns can cause far greater harm if misused or breached.

3. Risk to Data Principal rights

The likelihood that data processing could limit, override, or negatively affect a Data Principal’s rights, such as their ability to access, correct, or control how their data is used.

4. Potential impact on public order, sovereignty, or democracy

It evaluates whether misuse or compromise of personal data could influence public institutions, democratic processes, or national security.

This risk-based escalation leads to a distinct regulatory category – the Significant Data Fiduciary.

What Is a Significant Data Fiduciary (SDF)?

A Significant Data Fiduciary (SDF) is a Data Fiduciary that processes personal data at a scale or sensitivity that creates elevated risk to Data Principal rights, triggering additional obligations under the DPDP Act.

Factors considered for SDF designation include:

- Volume of personal data processed

- Sensitivity of personal data

- Risk to the rights of Data Principals

- Potential impact on sovereignty, public order, or democratic processes

Once notified, the entity is legally classified as an SDF.

This isn’t a title upgrade. It’s a responsibility upgrade.

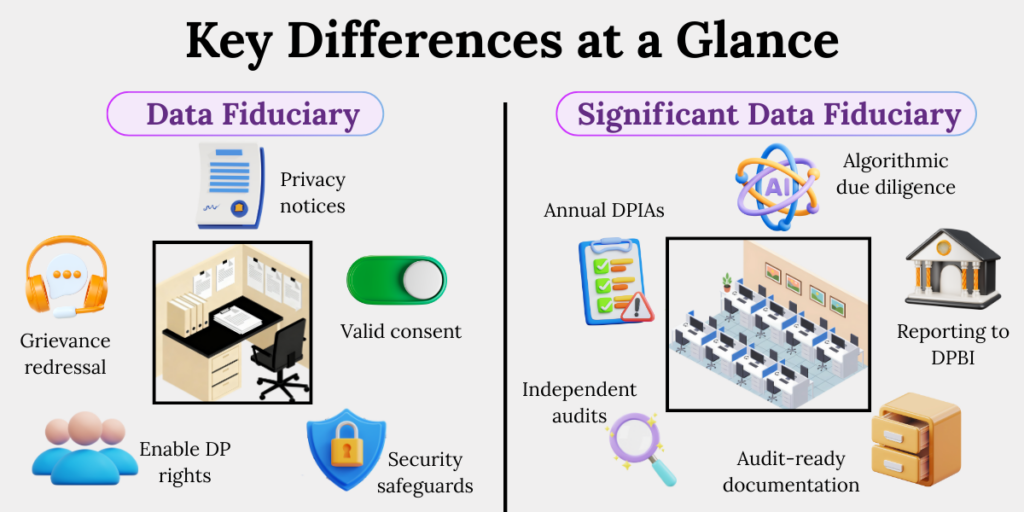

Data Fiduciary vs Significant Data Fiduciary

Under the DPDP Act, both Data Fiduciaries and Significant Data Fiduciaries must meet core compliance duties such as issuing privacy notices, obtaining valid consent, securing personal data, enabling Data Principal rights, reporting breaches, and resolving grievances.

The difference lies in scale and scrutiny.

While ordinary Data Fiduciaries operate under proportionate, largely internal compliance controls, Significant Data Fiduciaries are subject to heightened, continuous oversight.

SDFs must conduct mandatory annual DPIAs, undergo independent audits, perform algorithmic risk due diligence, maintain audit-ready documentation, and engage directly with the regulator through structured reporting.

In short: All SDFs are Data Fiduciaries—but not all Data Fiduciaries are regulated like SDFs.

Rule 13: Additional Obligations of Significant Data Fiduciaries

Rule 13 of the DPDP Rules, 2025 gives effect to the Central Government’s power to impose heightened, ongoing obligations on Significant Data Fiduciaries.

Rule 13 applies only after an entity is notified as an SDF.

The Rule mandates:

- Periodic impact assessments

- Annual independent audits

- Mandatory regulatory reporting

- Preventive governance for high-risk processing

Rule 13 transforms scale and sensitivity into continuous accountability.

Let’s break these obligations down further.

Mandatory Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)

A Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) is a structured check of how personal data is processed, what risks it creates for Data Principals, and whether existing safeguards are enough.

In simple terms, it answers one question: are we handling this data safely—or just hoping for the best?

Every Significant Data Fiduciary must conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) at least once every twelve months, starting from the date it becomes an SDF.

This is a statutory obligation, not a best practice.

What the DPIA must assess

The DPIA must evaluate whether the SDF’s processing:

- Legal compliance — Whether the processing aligns with the DPDP Act, applicable Rules, and lawful purpose limitations.

- Protection of Data Principal rights — Whether individuals can realistically exercise access, correction, erasure, and grievance rights without friction.

- Safeguard adequacy — Whether technical and organisational measures are proportionate to the nature, scale, and sensitivity of the data processed.

- Risk minimisation — Whether risks created by large-scale processing, sensitive data, or automated systems are identified, reduced, and controlled.

The focus is on impact, not intent.

If processing can adversely affect Data Principals, it must be assessed—even if no harm has yet occurred.

Once completed, the DPIA forms part of the SDF’s ongoing compliance record.

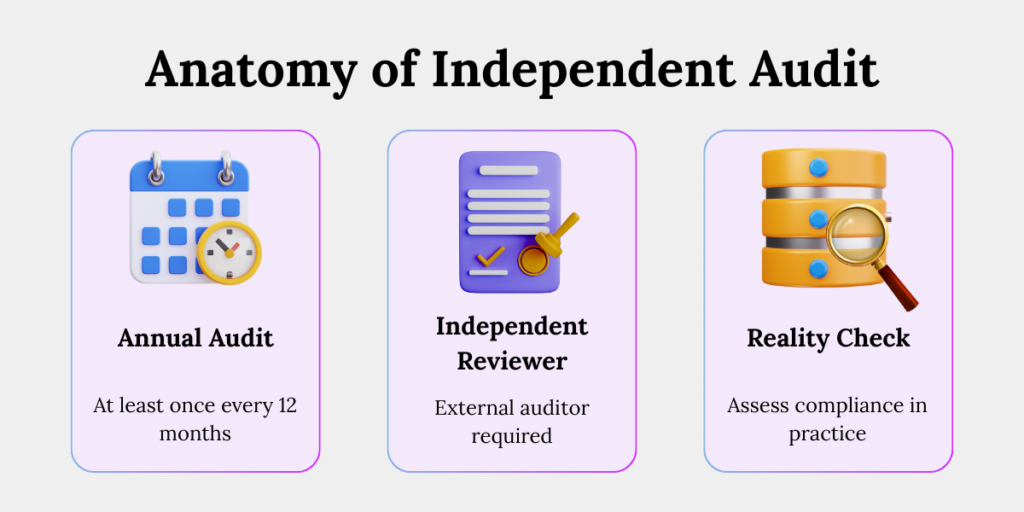

Independent Audit Requirements

An independent audit is an external review of whether an organisation is actually complying with the DPDP Act and Rules, not just claiming that it is.

In other words, someone who isn’t on your payroll checks the paperwork—and the reality.

Rule 13 makes independent audit of compliance mandatory for SDFs.

Key statutory features

- The audit must be conducted at least once every 12 months

- It must be carried out by a person independent of the SDF

- The audit must examine actual compliance, not policy statements

Scope of audit includes

- Lawfulness of processing — Whether personal data is being processed for lawful purposes, with valid consent or other permitted grounds, and in line with the DPDP Act and Rules.

- Governance and accountability structures — Whether internal roles, responsibilities, policies, and oversight mechanisms are clearly defined and actually followed.

- Implementation of DPDP obligations — Whether statutory duties such as notices, consent management, rights handling, breach reporting, and grievance redressal are operational in practice, not just documented.

- Effectiveness of safeguards — Whether technical and organisational measures genuinely protect personal data against misuse, unauthorised access, or breaches at the scale at which data is processed.

A Data Fiduciary is any person or entity that determines the purpose and means of processing personal data.

Self-certification is no longer sufficient. Rule 13 prefers verification over optimism.

Reporting Obligations to the Data Protection Board of India (DPBI)

The Data Protection Board of India (DPBI) is the statutory authority responsible for overseeing compliance and enforcing the DPDP Act.

Think of it as the regulator that shows up when compliance moves from policy to proof.

Rule 13 introduces direct regulatory visibility into SDF governance.

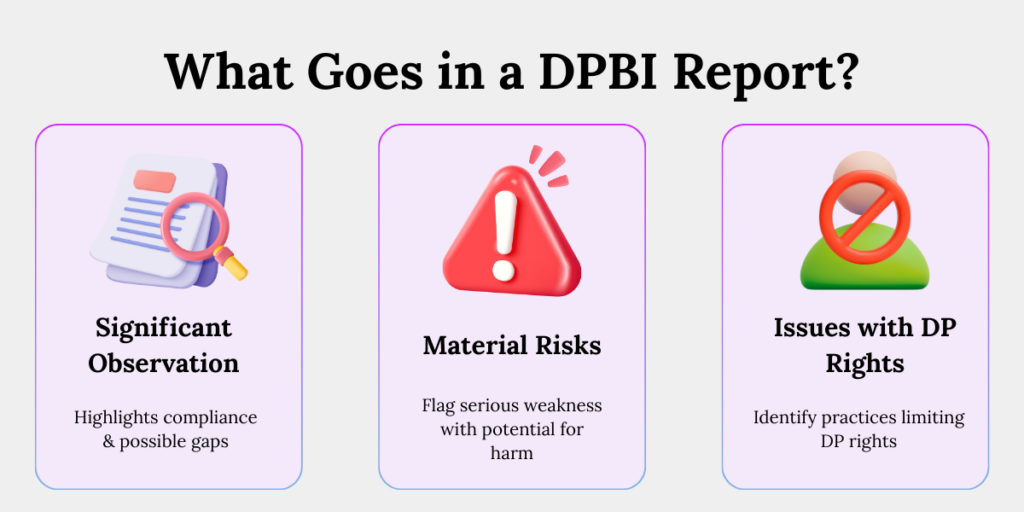

The person conducting the DPIA and audit must submit a report to the Data Protection Board of India (DPBI) containing:

- Significant observations — Key findings that indicate how well the organisation is complying with the DPDP Act and where meaningful gaps or concerns exist.

- Material risks or deficiencies — Serious weaknesses in processes, controls, or safeguards that could lead to non-compliance, data misuse, or harm if left unaddressed.

- Issues impacting Data Principal rights — Any practices or failures that may restrict, delay, or undermine a Data Principal’s ability to exercise their rights over personal data.

- Reporting is mandatory

- The threshold is significant observations, not proven violations

For SDFs, engagement with the regulator is proactive, not reactive. The idea is simple: show your workings before things go wrong — not after

Algorithmic and Technical Due Diligence

Rule 13 explicitly addresses algorithmic and automated processing risks.

In simple terms, algorithmic and technical due diligence means this:

SDFs must actively check whether the technology they use can harm Data Principals — before that harm actually happens.

Or put even more plainly: If your systems are making decisions about people’s data, you are responsible for how those decisions behave.

This due diligence is mandatory because automated systems can:

- Scale mistakes rapidly

- Make opaque decisions

- Impact rights without human intervention

And at SDF scale, even small flaws can affect millions.

What SDFs must verify

SDFs must undertake due diligence to verify that both technical measures and algorithmic software used for:

- Hosting

- Storing

- Processing

- Sharing personal data

do not pose a risk to the rights of Data Principals.

What counts as technical measures?

Technical measures include safeguards such as:

- Access controls (role-based access, least-privilege permissions)

- Encryption (data at rest and in transit)

- Logging and monitoring systems

- Automated decision engines and scoring models

- AI or ML systems used for profiling, recommendations, or eligibility checks

(If a system touches personal data and “decides” something — it’s in scope.)

This applies regardless of whether systems are:

- Built internally, or

- Procured from third parties

Rule 13 makes it clear: scale and automation increase responsibility, not excuses. Responsibility cannot be outsourced.

Because “the algorithm did it” is not a legally acceptable defence anymore.

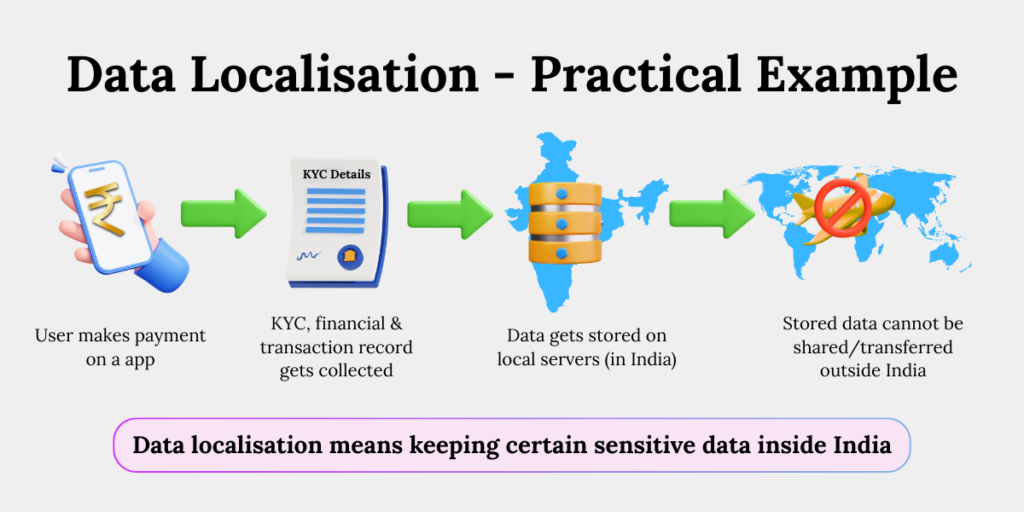

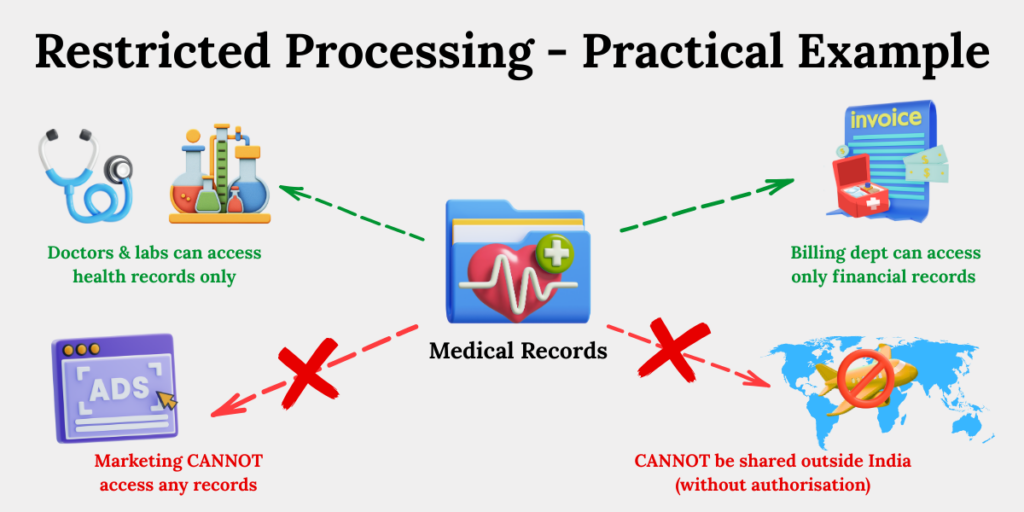

Data Localisation and Restricted Processing

Data localisation means keeping certain personal data within India.

Restricted processing means limiting how, where, or by whom specific data can be processed or transferred.

In short: some data is too sensitive to move freely or be processed anywhere without limits.

Rule 13 empowers the Central Government to impose processing and transfer restrictions on specified categories of personal data.

The Government, based on committee recommendations, can specify:

- Certain categories of personal data, and

- Related traffic data

that an SDF must ensure is processed in a manner that prevents transfer outside India.

This is selective and binding, not blanket localisation.

It means:

- Only clearly identified categories of personal data are covered

- Restrictions apply only when formally prescribed by the government

- Once prescribed, compliance is mandatory

- SDFs cannot bypass these restrictions through contracts, consent, or technical workarounds

Think of it as a targeted lockdown, not a nationwide curfew — precise, deliberate, and enforceable.

For SDFs, cross-border data handling is a governance decision — not just a technical one.

Governance, Documentation, and Accountability

Rule 13 operates on a simple principle: demonstrable compliance.

Demonstrable compliance means SDFs must be able to prove they are complying — not just claim that they are.

Compliance must be visible, provable, and documented

SDFs must be able to produce:

1. DPIA records

These are documented assessments showing what personal data is processed, why it is needed, what risks it creates for Data Principals, and how those risks are mitigated.

These records prove that privacy risks were identified and addressed before harm occurred.

2. Audit reports

This is an independent evaluation confirming whether DPDP obligations are actually being followed in practice.

These reports help demonstrate that compliance is verified externally, not just claimed internally.

3. Due diligence documentation

Written evidence showing how the organisation evaluated its systems, vendors, tools, and algorithms to ensure they do not harm Data Principal rights.

This helps show that automation and technology choices were made responsibly.

4. Governance decisions

Clear records of who took key data protection decisions, why they were taken, and how accountability was assigned.

These ensure compliance decisions are traceable to leadership—not buried in IT operations.

If it is not documented, it did not happen. And undocumented compliance does not survive audits.

Enforcement Risk and Penalty Exposure

Rule 13 compliance is demanding by design — and treating it lightly is where organisations get into real trouble.

Failure to comply with Rule 13 exposes SDFs to:

1. Regulatory scrutiny by the DPBI

Deficiencies flagged in audits or DPIAs can trigger inquiries, directions, corrective orders, and continued monitoring by the Data Protection Board of India.

2. Penalties under the DPDP Act

Non-compliance may attract penalties under the DPDP Act that can go up to ₹250 crore, depending on the nature, scale, and impact of the violation.

3. Heightened compliance oversight

Once an SDF is found non-compliant, future processing activities may face stricter reviews, repeated audits, and deeper regulatory intervention.

4. Reputational damage

For large platforms and data-intensive businesses, enforcement action can result in loss of user trust, partner confidence, and public credibility — damage that penalties alone cannot fix.

5. Operational disruption

Corrective directions may require changes to data architecture, algorithms, cross-border transfers, or governance structures, often under tight regulatory timelines.

When you handle data at scale, regulators don’t offer leniency — they bring a magnifying glass.

Practical Compliance Takeaways for SDFs

If your organisation is—or may soon be—classified as an SDF, priorities are clear:

- Institutionalise annual DPIAs: Make DPIAs a recurring internal exercise to regularly assess privacy risks, not a one-time compliance checkbox.

- Build audit-ready governance: Put policies, roles, approvals, and documentation in place so audits can be faced confidently, without last-minute scrambling.

- Conduct algorithmic risk reviews: Periodically review automated systems and algorithms to ensure they do not unfairly harm or disadvantage Data Principals.

- Re-evaluate data localisation architecture: Assess where personal data is stored and processed to ensure cross-border flows align with government restrictions.

- Prepare for direct regulatory reporting: Set up internal processes to generate clear, accurate reports that can be submitted directly to the Data Protection Board when required.

Rule 13 is not about ticking boxes. It is about proving that you deserve the trust you control.

Conclusion

For Significant Data Fiduciaries, Rule 13 turns data protection into a continuous governance obligation.

It demands visibility, verification, and preparedness — not just policies on paper.

At scale, trust is earned by proving compliance, year after year.

Key Takeaways

- The DPDP Act applies to all Data Fiduciaries, but entities handling data at scale face higher accountability.

- Significant Data Fiduciaries are subject to stricter, ongoing obligations due to increased risk to individuals and society.

- Rule 13 mandates annual DPIAs to proactively assess privacy risks and safeguard Data Principal rights.

- Independent audits are compulsory to externally verify real-world DPDP compliance.

- SDFs must report key audit and DPIA findings directly to the Data Protection Board of India.

- Automated systems and algorithms must be actively reviewed to prevent harm at scale.

- Certain sensitive data may be restricted to India, making cross-border data handling a governance decision.

- Documentation, audits, and records are essential. Compliance must be provable, not assumed.