Why DPDP Matters in the Healthcare Sector

Healthcare compliance doesn’t usually break in courtrooms.

It breaks quietly inside hospitals, labs, clinics, and health-tech platforms—where data flows faster than governance.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP Act) forces a reset. For healthcare, this law is not about paperwork. It is about rebuilding trust, control, and accountability around patient data—before breaches, penalties, or reputational damage make the decision for you.

This blog explains why DPDP matters in the healthcare sector and what a practical compliance blueprint looks like in real operations.

Why DPDP is critical for healthcare organisations

DPDP is critical for healthcare organisations because they process large volumes of sensitive personal data such as medical records, diagnostics, biometrics, and children’s data. Any misuse or breach directly impacts patients and trust. DPDP forces hospitals and health-tech companies to shift from informal data handling to strict, system-level accountability.

Healthcare data is different.

It is intimate, permanent, and impossible to reset once exposed.

We consistently observe that healthcare organisations hold significantly more sensitive data per individual than most other industries—clinical history, diagnostics, insurance details, and caregiver notes combined.

This concentration of risk is exactly why DPDP applies pressure here first.

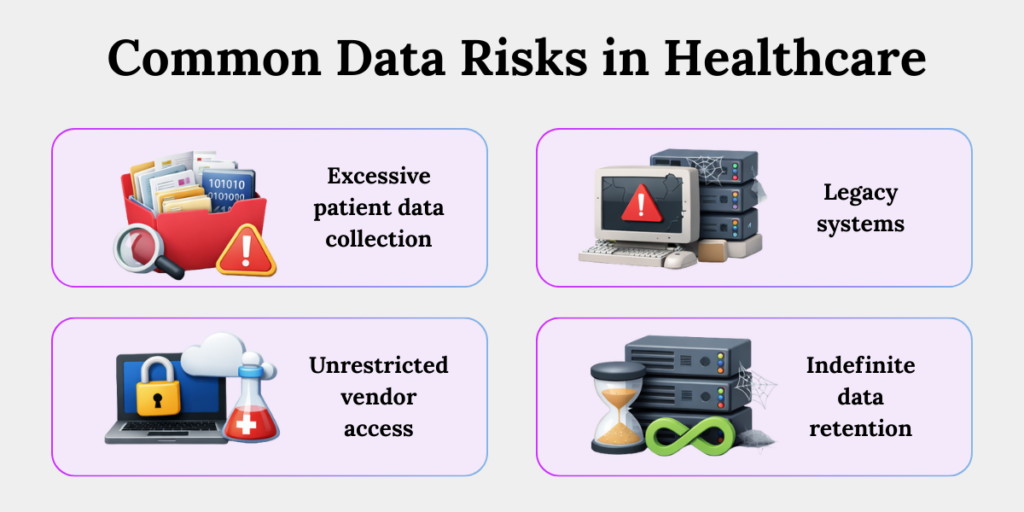

Data Risks in Healthcare

DPDP is designed to address common healthcare data risks such as unnecessary data collection, outdated systems storing patient records, uncontrolled vendor access, and indefinite data retention. These risks increase the likelihood of breaches and misuse. DPDP targets these failures by enforcing purpose, control, and accountability at an operational level.

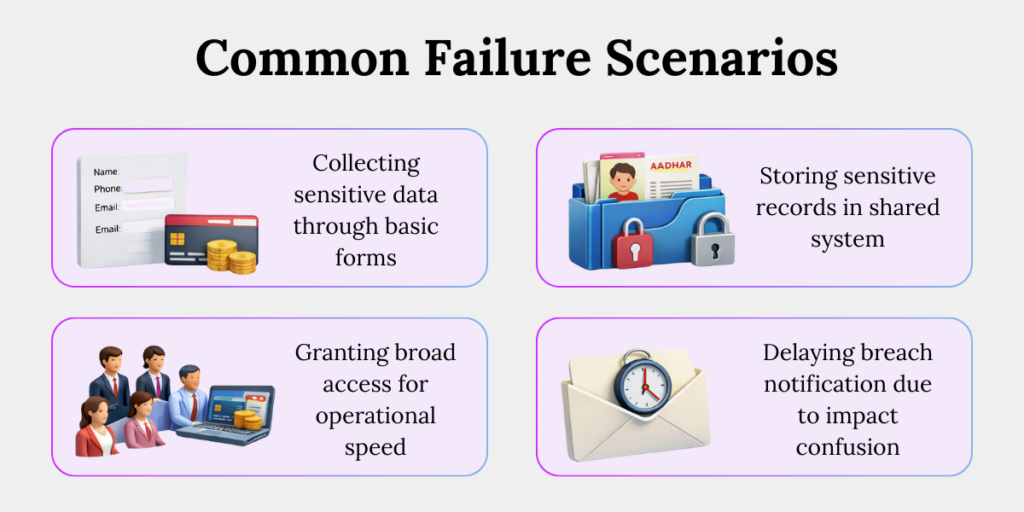

Healthcare data problems are rarely malicious.

They are architectural.

1. Patient data collected “just in case”

Healthcare teams often collect more data than required to avoid future clinical uncertainty or rework. Over time, this creates bloated databases with no clear purpose, increasing breach impact and directly violating DPDP’s purpose limitation requirement.

2. Legacy systems still active after replacement

Old hospital systems are frequently left running after upgrades. These systems quietly continue storing patient data without monitoring or security updates, becoming invisible compliance and breach risks.

3. Diagnostic vendors with unrestricted access

Labs and imaging partners are often given broad system access for operational convenience. Without strict controls, vendors can access or retain patient data far beyond what diagnostics require.

4. No clear retention or deletion triggers

Medical data is commonly stored indefinitely due to legal caution or operational neglect. Without enforced deletion rules, outdated data accumulates, increasing long-term exposure under DPDP.

Purpose Limitation: Toughest DPDP Challenge for Hospitals

Purpose limitation is the toughest DPDP challenge for hospitals because patient data is routinely reused across treatment, billing, analytics, and research without strict boundaries. DPDP requires hospitals to clearly define why data is collected and technically prevent reuse beyond that purpose unless explicitly authorised.

Purpose limitation sounds simple.

In healthcare, it is operationally unforgiving.

A common hospital scenario:

A hospital collects blood test results strictly for diagnosis and treatment. Later, the same data is pulled into an internal analytics project to study patient trends—without updating the purpose or seeking fresh consent.

No data is “leaked.”

Nothing looks unsafe.

But under DPDP, this is a violation—because data collected for treatment quietly crossed into analytics without authorisation. Purpose limitation fails not when systems break, but when boundaries are ignored.

DPDP expects purpose to be enforced through systems, not explained away in policies.

Think of it as a locked room—if the key does not match the purpose, access must fail.

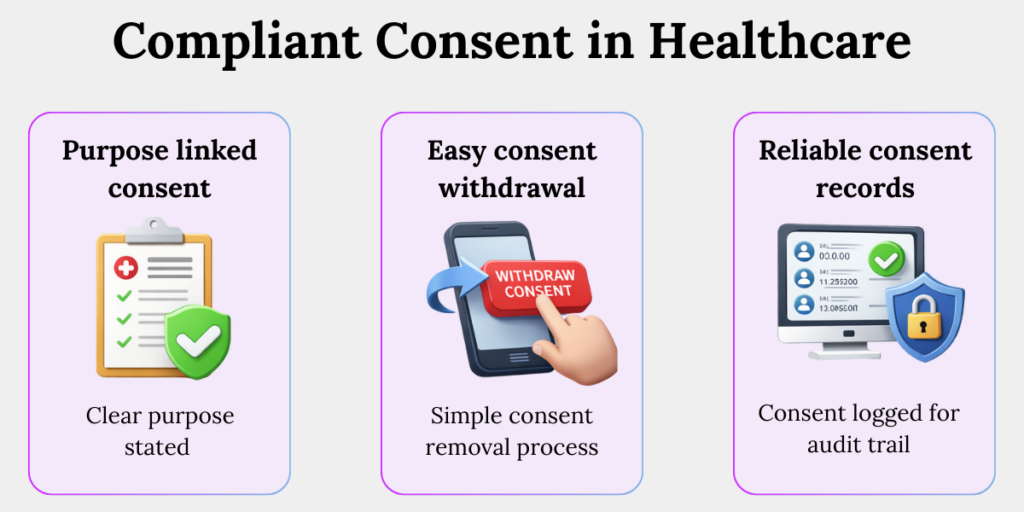

Consent in Healthcare Operations

Consent in healthcare operations under DPDP must be specific, purpose-linked, revocable, and provable. Traditional admission forms or blanket consents are no longer sufficient. Hospitals must operationalise consent through systems that record, enforce, and respect patient choices across data flows.

Consent in healthcare has historically been procedural.

DPDP turns it into evidence.

Here’s what a DPDP compliant consent in healthcare sectors looks like

1. Purpose-linked consent

Consent must clearly state why patient data is collected and how it will be used. This prevents silent reuse of medical data for unrelated activities such as marketing or analytics.

2. Easy consent withdrawal

Patients must be able to withdraw consent as easily as they gave it. This ensures real control over personal data and prevents consent from becoming a one-time, irreversible checkbox.

3. Reliable consent records

Healthcare systems must log when consent was obtained, for which purpose, and any changes made later. These records become critical proof during audits or breach investigations.

Children’s Data, Healthcare, and DPDP Compliance

Healthcare frequently involves children’s data through paediatric care, vaccinations, diagnostics, and school-linked health programs. DPDP applies stricter rules to such data, including verifiable parental consent and limits on tracking and profiling. This makes DPDP compliance unavoidable for most healthcare providers.

A familiar healthcare scenario:

A paediatric clinic uses a mobile app to share vaccination schedules and test reports with parents. During onboarding, the clinic collects the child’s details and the parent’s phone number—but does not verify whether the consent actually came from a lawful guardian.

The app later tracks usage to “improve engagement.”

Under DPDP, this becomes non-compliant processing of children’s data.

What feels like routine digital care delivery turns into a compliance gap—because parental consent was assumed, not verified, and tracking was never restricted.

DPDP effectively raises the bar: if you cannot prove parental consent and restrict usage, you cannot lawfully process the data.

There is no operational shortcut here.

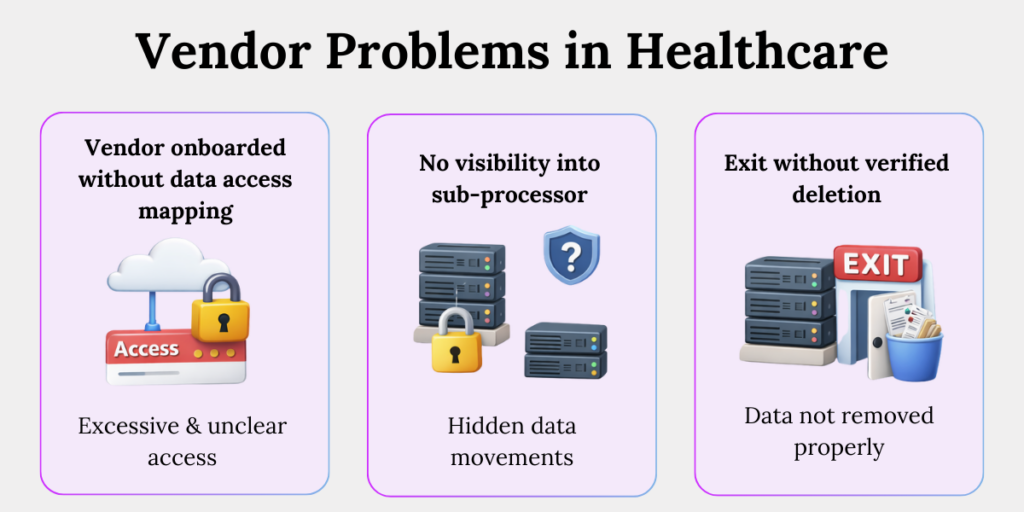

How Vendors Create DPDP Compliance Risk in Healthcare

Healthcare organisations depend heavily on vendors such as EHR providers, labs, and cloud platforms. DPDP holds the healthcare entity responsible for vendor-related data failures. Weak onboarding, poor visibility, and improper exits turn vendors into one of the biggest compliance risks in healthcare.

A common real-world scenario:

A hospital uses an external diagnostic lab to process blood tests. To “speed things up,” the lab is given broad access to the hospital’s patient management system instead of limited, test-specific access. Over time, the lab stores copies of patient reports on its own servers.

The contract ends. Access is disabled—but the data isn’t deleted.

Months later, the lab suffers a breach. Patients are affected.

Under DPDP, the hospital remains accountable, because it never restricted access, tracked data movement, or verified deletion at exit.

This is how vendor convenience quietly becomes a compliance failure.

Vendor management problems in healthcare sector includes:

1. Vendors onboarded without data access mapping

Vendors are often granted system access without clearly defining what data they actually need. This leads to excessive access that is difficult to justify under DPDP.

2. No visibility into sub-processors

Primary vendors frequently rely on sub-vendors without the hospital’s knowledge. Patient data moves beyond approved boundaries, creating blind spots in accountability.

3. Exit without verified deletion

When vendor contracts end, data deletion is rarely confirmed. Patient data may continue to exist in external systems, creating long-term compliance and breach risks.

Practical DPDP Compliance Blueprint for the Healthcare Sector

A practical DPDP compliance blueprint for the healthcare sector focuses on operational controls rather than policies. It includes mapping data flows, enforcing purpose at system level, managing consent dynamically, controlling access, defining retention, and preparing for breaches. Compliance works when privacy is engineered into daily operations.

This is where theory ends.

Execution begins.

1. Map healthcare data flows

Document how patient data moves across hospitals, labs, applications, and vendors. Visibility is the foundation for control, breach response, and accountability.

2. Bind purposes to systems

Embed purpose limitation directly into workflows and applications instead of relying on policy documents. This prevents unauthorised reuse of patient data.

3. Enforce role-based access

Restrict data access based on clinical, administrative, and technical roles. This limits internal misuse and strengthens audit defensibility.

4. Automate consent management

Use systems to capture, update, and enforce consent choices in real time. Automation ensures patient preferences are consistently respected.

5. Define retention and deletion triggers

Set clear rules for how long medical data is retained based on treatment and legal needs. Enforced deletion reduces long-term exposure.

6.Prepare breach response playbooks

Define internal timelines, roles, and escalation paths for data breaches. Fast, coordinated responses matter under DPDP.

Conclusion

DPDP does not ask healthcare organisations to write better policies.

It asks them to build better systems.

DPDP expects healthcare leaders to move beyond policies and implement system-level controls for how patient data is collected, used, shared, and deleted.

Organisations that act early reduce regulatory risk and improve accountability.

Those that delay face higher exposure during audits, breaches, and enforcement.

Key Takeaways

- DPDP matters in healthcare because hospitals and health-tech companies handle large volumes of sensitive and children’s personal data.

- Healthcare data risks often come from operational gaps such as excessive data collection, legacy systems, and unclear retention practices.

- Purpose limitation is difficult in healthcare because patient data is frequently reused across treatment, analytics, and research without clear boundaries.

- DPDP requires consent in healthcare to be specific, provable, and easy for patients to withdraw.

- Children’s data triggers stricter DPDP obligations, making verified parental consent and usage controls essential.

- Vendors create significant DPDP risk when access, sub-processing, and data deletion are not tightly controlled.

- DPDP compliance succeeds in healthcare only when privacy controls are built into daily operations, not handled through policies alone.