Common Challenges in DPDP Compliance

DPDP compliance rarely fails because organisations ignore the law.

It fails because daily operations move faster than governance. Personal data spreads across tools, teams, and vendors, while compliance remains trapped in policies and intent. These common challenges in DPDP compliance are operational, predictable, and entirely fixable – if addressed early and systematically.

This blog explains where DPDP compliance usually fails in real organisations and shows how to fix these issues through practical, system-level actions.

What Are the Most Common Challenges in DPDP Compliance?

The most common DPDP compliance challenges stem from operational blind spots rather than legal confusion. Organisations struggle with data visibility, consent enforcement, security safeguards, breach readiness, retention discipline, and vendor oversight. These issues appear consistently across sectors and directly weaken compliance outcomes.

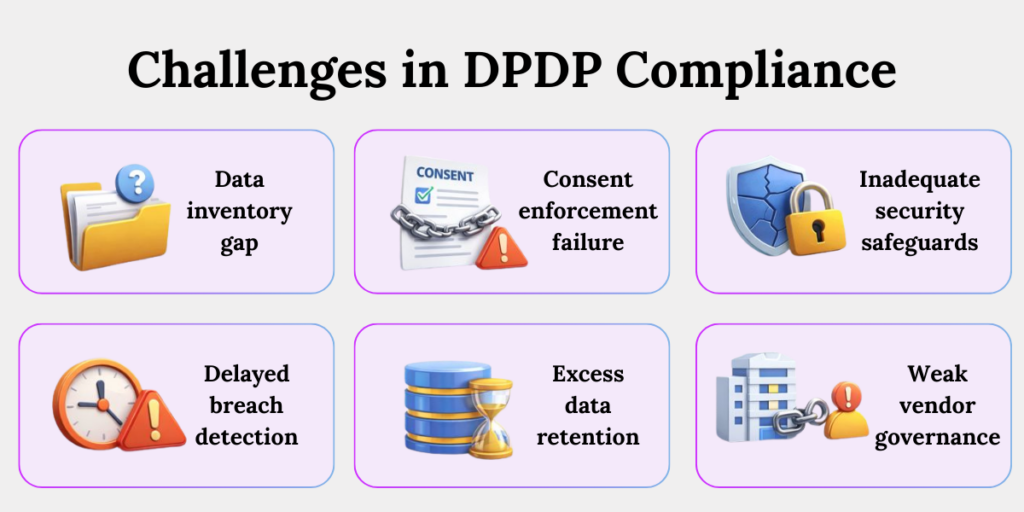

The most common DPDP compliance challenges include:

- Data inventory gaps

- Consent enforcement failure

- Inadequate security safeguards

- Delayed breach detection

- Excessive data retention

- Weak vendor governance

Each challenge below explains how DPDP fails in practice and what to build instead.

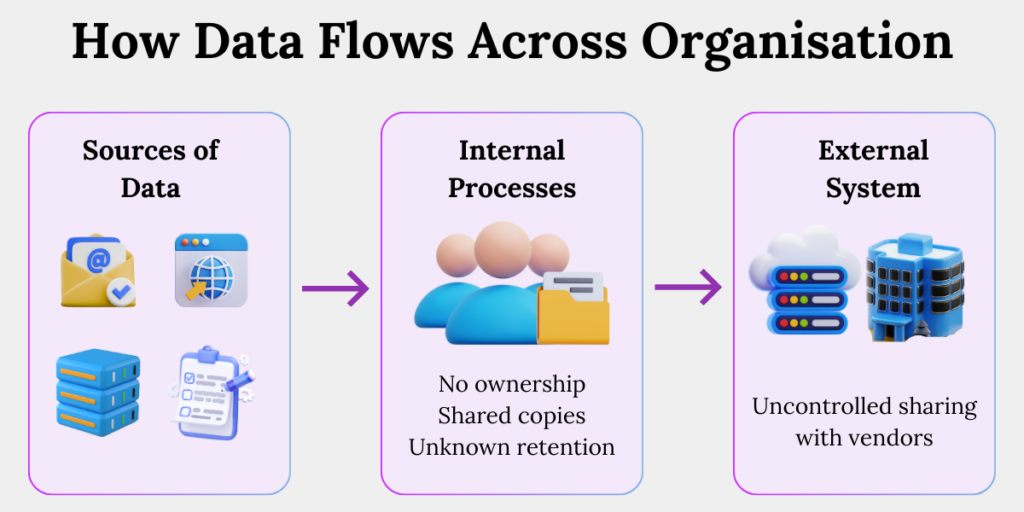

Challenge 1: Limited Visibility Into Personal Data

A foundational DPDP compliance challenge is the absence of complete visibility into personal data across systems, teams, and vendors. Without knowing what data exists, why it was collected, and who accesses it, organisations cannot enforce retention limits, consent conditions, or security safeguards effectively.

You cannot protect what you cannot see.

And most organisations are operating with partial maps and full confidence.

How this fails in practice

1.Personal data is collected through multiple unconnected entry points.

Sales teams capture leads in CRMs, marketing collects data through campaigns, and support teams receive documents over email. These systems rarely talk to each other, creating fragmented and duplicated datasets.

2. Employee inboxes and shared drives become shadow databases.

Identity proofs, complaints, and verification documents are stored for convenience and never formally tracked. Over time, these locations are forgotten but remain accessible.

3. No one owns the full data lifecycle.

Teams know they use data, but no one is responsible for deciding how long it should exist, when it should be deleted, or who should lose access.

4. Vendors quietly expand the data footprint.

Once data is shared externally, copies multiply across third-party systems with little ongoing visibility or control.

Practical Blueprint

1. Build a Living Data Inventory

Create a central record of all personal data categories, including source, purpose, storage location, and owner. Update it regularly so it reflects reality, not assumptions.

2. Classify Data by Sensitivity and Purpose

Differentiate basic identifiers from sensitive data. This determines security controls, retention timelines, and breach impact.

3. Assign Clear Data Ownership

Every dataset must have a named owner accountable for access approvals, retention enforcement, and deletion decisions.

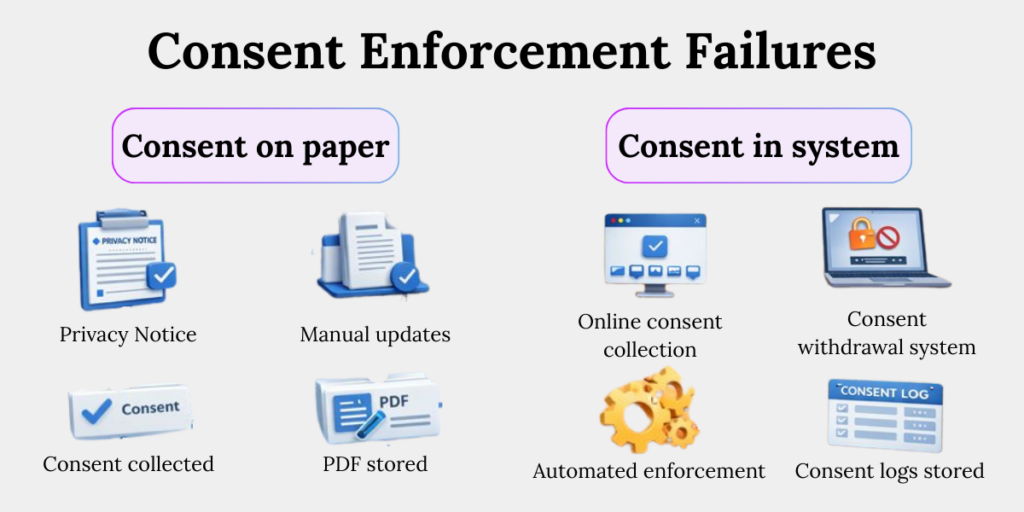

Challenge 2: Consent That Cannot Be Enforced

Many organisations collect consent but lack the technical ability to enforce it across systems. DPDP requires consent to be specific, traceable, and revocable, yet most businesses rely on static records that do not control downstream data usage.

Consent is not a form.

It is a system control.

How this fails in practice

1. Consent is captured once and never revisited.

Most organisations collect consent at the time of onboarding and treat it as permanent. When new tools, features, or internal processes are later introduced, teams continue using the same data without checking whether the original consent still applies to these new uses.

2. Consent withdrawal does not trigger system changes.

When a user withdraws consent through email, a support ticket, or a form, the request is often handled manually. While the request may be acknowledged, the underlying systems are not updated, so personal data continues to be processed as before.

3. Purpose limitation erodes quietly.

Data collected for a specific purpose, such as providing a service or fulfilling a transaction, is gradually reused for analytics, internal testing, or marketing. This reuse happens without verifying whether the original consent covers these additional purposes.

4. Proof of enforcement is missing during audits.

During audits or regulatory reviews, organisations can present privacy notices and consent language. However, they are unable to show system-level evidence that processing actually stopped or changed after consent was withdrawn or modified.

Practical Blueprint

1. Tie Consent to Processing Purpose

Each consent record should clearly specify what the data can be used for and which systems are allowed to process it. This ensures consent is enforceable at a system level rather than remaining a legal statement.

2.Automate Consent Propagation

Consent withdrawal should automatically trigger restrictions across all systems and vendors that process the data. This removes reliance on manual follow-ups and reduces the risk of continued unauthorised processing.

3. Maintain Verifiable Consent Logs

Organisations should maintain tamper-proof logs that record when consent was given, changed, or withdrawn. These logs should include timestamps, purposes, and affected systems to demonstrate compliance during audits

Challenge 3: Inadequate Security Safeguards

DPDP compliance fails when organisations equate encryption with security. Regulators expect layered safeguards, including access governance, monitoring, and breach preparedness. Encryption alone does not prevent internal misuse, misconfiguration, or delayed detection.

Security is not a lock.

It is a patrol.

How this fails in practice

1. Access expands faster than governance.

As employees change roles or take on new responsibilities, they are given additional system access to do their work. Over time, older permissions are rarely removed, resulting in employees having access to far more personal data than they actually need.

2. Logs are generated but ignored.

Most systems automatically generate access and activity logs, but these logs are rarely reviewed on an ongoing basis. Without regular monitoring, unusual access patterns or misuse of personal data go unnoticed until an incident occurs.

3. All data is protected the same way.

Organisations often apply the same security controls to all data, regardless of sensitivity. As a result, highly sensitive personal data is not given additional protection, even though its misuse or exposure would have significantly higher impact.

4. Vendor access remains persistent.

Vendors are granted access to systems for specific projects or services, but that access is rarely reviewed or revoked once the work is complete. Over time, this creates unnecessary external access to personal data and increases security risk.

Practical Blueprint

1. Enforce Role-Based Access Controls

Grant system access strictly based on an employee’s current role and responsibilities. Regularly review and remove permissions that are no longer required to ensure access remains limited and appropriate.

2. Monitor Logs Continuously

Assign clear responsibility for reviewing security logs on a regular basis. Use logs to identify unusual access, repeated failures, or unexpected data activity before they escalate into breaches

3. Apply Risk-Based Security Layers

Apply stronger controls to sensitive personal data, such as multi-factor authentication, tighter access restrictions, and enhanced monitoring. Lower-risk data can be protected with proportionate safeguards to balance security and usability.

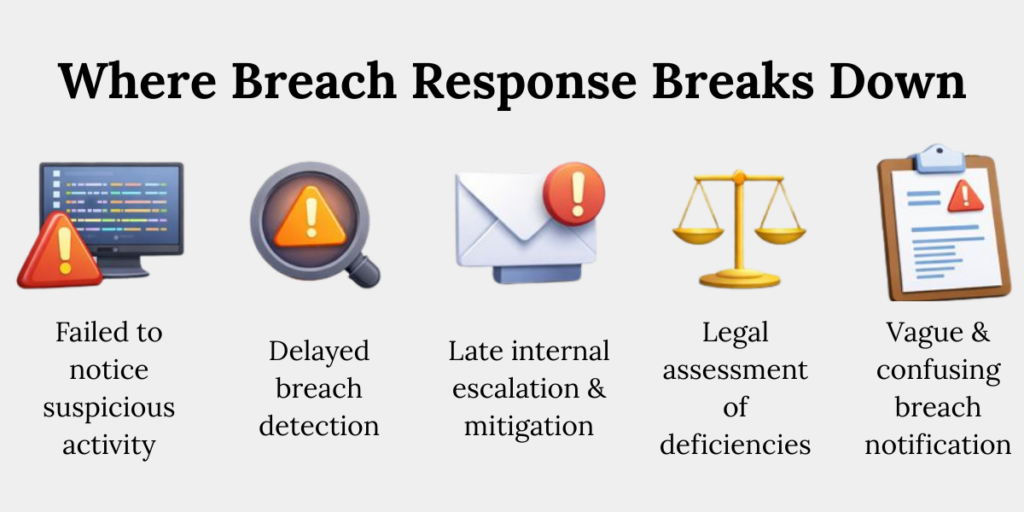

Challenge 4: Delayed Breach Detection and Response

Most organisations miss DPDP breach timelines because incidents are detected too late. Breach response plans exist on paper, but teams lack clarity on detection thresholds, escalation paths, and decision ownership.

Breaches rarely arrive with sirens.

They arrive quietly.

How this fails in practice

1. Teams don’t recognise breaches early.

Unusual system behaviour such as repeated login failures, large data downloads, or access outside normal hours is often treated as routine activity. Without clear guidance on what signals indicate a potential breach, these warning signs are ignored until the situation worsens.

2. Escalation depends on individuals.

Incident reporting often relies on personal judgment rather than defined rules. If a vigilant employee notices an issue, it may be escalated quickly, but if not, the same issue can remain unreported for days.

3. Legal and compliance teams are informed too late.

Technical teams usually try to fix the issue first by blocking access or resetting systems. Legal and compliance teams are brought in only after these actions, which delays assessment of notification obligations and increases regulatory risk.

4. Plans are untested.

Organisations may have incident response plans on paper, but teams have never practiced using them. During a real incident, this leads to confusion about roles, timelines, and communication responsibilities.

Practical Blueprint

1. Define Breach Awareness Thresholds

Clearly document what events should be treated as potential breaches, such as unauthorised access, data exfiltration, or system compromise. This removes ambiguity and ensures issues are escalated consistently.

2. Assign Clear Incident Ownership

Define in advance who is responsible for investigation, decision-making, and communication during an incident. This avoids delays caused by uncertainty and overlapping responsibilities.

3. Run Regular Breach Simulations

Conduct periodic drills to test detection, escalation, and reporting processes. Simulations help teams identify gaps early and ensure everyone understands their role before a real incident occurs.

Challenge 5: Excessive Data Retention

Retaining personal data beyond its purpose directly violates DPDP’s storage limitation principle. Organisations often retain data indefinitely due to habit, fear, or lack of automation, increasing compliance and breach risk.

More data feels safer.

It isn’t.

How this fails in practice

1. Retention decisions are driven by uncertainty.

Teams are unsure how long personal data is legally or operationally required, so they choose the safest option from their perspective – keeping it indefinitely. Over time, this results in large volumes of unnecessary personal data being stored without a valid purpose.

2. Deletion is fragmented and incomplete.

Data may be deleted from primary business systems, but copies continue to exist in email inboxes, backups, archives, and shared drives. Because deletion is not coordinated across all storage locations, organisations assume data is gone when it is not.

3. Retention policies are not enforced.

Retention rules are documented in policies, but there is no regular process to check whether those rules are followed. As a result, outdated personal data continues to exist long after it should have been erased.

Practical Blueprint

1.Define Purpose-Based Retention Rules

For every category of personal data, clearly define how long it is required based on the purpose of collection. Retention periods should be practical, documented, and understood by the teams that handle the data.

2. Automate Deletion and Anonymisation

Implement system-level controls that automatically delete or anonymise data once retention periods expire. Automation reduces the risk of missed deletions caused by manual processes.

3. Audit Retention Exceptions

Periodically review any data retained beyond standard timelines and document the business or legal justification. This ensures extended retention is deliberate and defensible, not accidental.

Challenge 6: Weak Vendor Governance

Third-party vendors frequently introduce DPDP non-compliance due to weak oversight. While processing may be outsourced, liability remains with the data fiduciary, making vendor governance a critical compliance control.

You can outsource processing.

You cannot outsource responsibility.

How this fails in practice

1. Vendor access expands informally.

Vendors are initially given limited access for a specific task or project. Over time, as new requirements are added, additional access is granted informally to avoid delays. This access is rarely reviewed, resulting in vendors having broader and longer access to personal data than originally intended.

2. Contracts lack enforceable DPDP controls.

Many vendor contracts include generic privacy clauses, but they do not clearly define security expectations, breach reporting timelines, or audit rights. As a result, even when obligations exist on paper, organisations struggle to enforce them in practice.

3. Vendor risk is assumed, not verified.

Once onboarding is complete, vendors are often trusted to remain compliant without ongoing checks. Organisations assume security controls are in place but do not actively verify access controls, data handling practices, or incident readiness.

Practical Blueprint

1. Assess Vendor Access Regularly

Review vendor access at defined intervals to ensure it is limited to what is strictly necessary for service delivery. Remove permissions that are no longer required due to role changes or project completion.

2. Embed DPDP Obligations Contractually

Update vendor agreements to clearly define security safeguards, breach notification timelines, data handling responsibilities, and audit rights. This ensures DPDP obligations are enforceable, not just implied.

3. Monitor High-Risk Vendors Periodically

Identify vendors that process sensitive or large volumes of personal data and review their compliance posture regularly. Monitoring should include access reviews, security checks, and confirmation of breach readiness.

Conclusion: DPDP Compliance Is Built, Not Declared

DPDP compliance fails when personal data is handled without clear ownership, system controls, or regular review. The common issues – poor data visibility, weak consent enforcement, security gaps, delayed breach response, excessive retention, and unmanaged vendors – are all operational failures.

Organisations that succeed under DPDP embed compliance into everyday processes, not just policies. They make compliance measurable, repeatable, and defensible.

That is the difference between having DPDP documentation and actually being DPDP compliant.

Key Takeaways

- DPDP compliance challenges are operational, arising from everyday data handling, not legal misunderstanding.

- Poor data visibility weakens enforcement of consent, security safeguards, and retention obligations.

- Consent compliance fails when consent cannot be enforced, withdrawn, or proven at a system level.

- Security and breach risks increase without access controls, monitoring, and clear incident ownership.

- Excessive data retention and weak vendor governance significantly increase DPDP compliance exposure.

- Effective DPDP compliance is system-driven, making it auditable, repeatable, and defensible.