Common Mistakes in Data Privacy Compliance

Data privacy compliance rarely collapses because of bad intent.

It collapses because of bad execution.

Across audits, breach investigations, and regulatory reviews, the same issue appears repeatedly: organisations invest in policies, tools, and certifications but fail to implement the operational controls that actually secure personal data. The result is a compliance framework that looks robust on paper but fails under real-world scrutiny.

This blog outlines the most common data privacy mistakes, why they occur and the practical steps to fix them before gaps turn into risk.

Why Do Organisations Keep Making the Same Data Privacy Mistakes?

Most data privacy failures stem from treating compliance as documentation instead of operations. Organisations focus on policies, notices, and checklists while ignoring data flows, access controls, vendor exposure, and deletion discipline. Regulators increasingly penalise this gap between “policy compliance” and “operational reality.”

This isn’t ignorance.

It’s misaligned priorities.

In our observations across multiple compliance programs, leadership often assumes that having policies equals being compliant. It doesn’t. Policies are the blueprint. Controls are the concrete and steel.

Ask yourself this:

If a regulator walked through your systems – not your documents – would your controls tell the same story?

Common Data Privacy Compliance Mistakes

Now let’s look at where things usually break down – the recurring data privacy mistakes that turn strong intentions into weak defences.

At a high level, these failures usually fall into six categories:

- Confusing policies with protection

- Not knowing where all personal data lives

- Treating consent as a checkbox exercise

- Ignoring vendor & third-party risk

- Keeping data ‘just-in-case’

- Being unprepared for a data breach

Let’s look at these mistakes in detail.

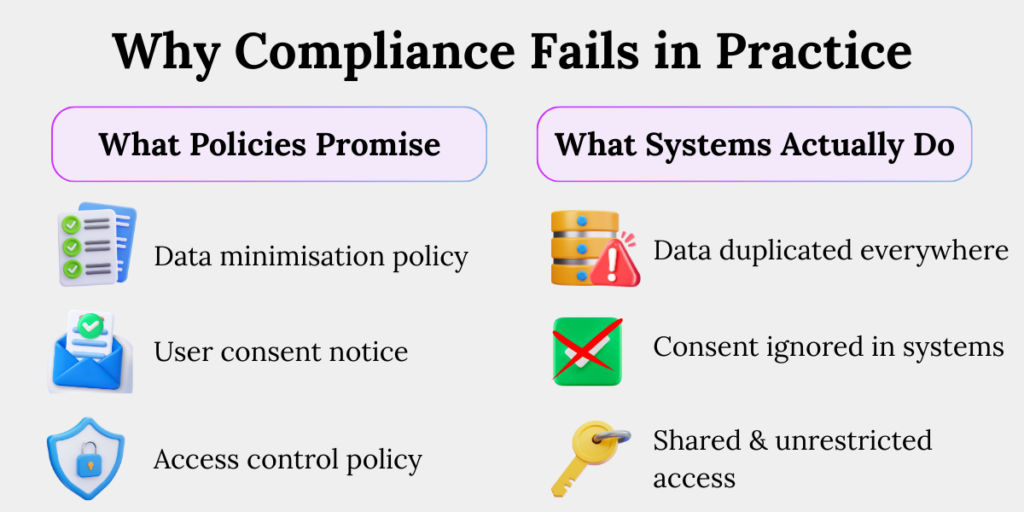

Mistake 1: Confusing Policies With Protection

A published privacy policy does not protect personal data. Regulators assess whether stated commitments are enforced through technical and organisational measures. When policies promise minimisation, consent, or deletion but systems cannot enforce them, organisations face penalties for misrepresentation and weak safeguards.

Policies are promises.

Controls are proof.

We routinely see organisations with beautifully written privacy notices that no system can actually implement. Data is still copied across tools. Access remains unchecked. Deletion is manual – or worse, forgotten.

How this fails in practice

- Purpose limitation exists only on paper

Policies clearly state why data is collected, but systems do not restrict how that data is reused. Teams access and repurpose personal data across departments without checks, breaking purpose limitation in day-to-day operations. - Deletion is promised but not executable

- Access rules are declarative, not enforced

Policies define who should access data, but access controls are role-based only in theory. In practice, shared credentials, broad permissions, and legacy access remain untouched.

Fix the architecture:

- Map policy promises to system controls

Every commitment in a privacy notice must correspond to a technical or operational control. If a promise cannot be enforced by design, it creates regulatory exposure. - Block unauthorised data use at the system level

- Automate deletion across environments

Deletion must propagate across primary systems, replicas, analytics tools, and backups. Manual deletion guarantees inconsistency and audit failure.

If a promise can’t be enforced, it shouldn’t be published.

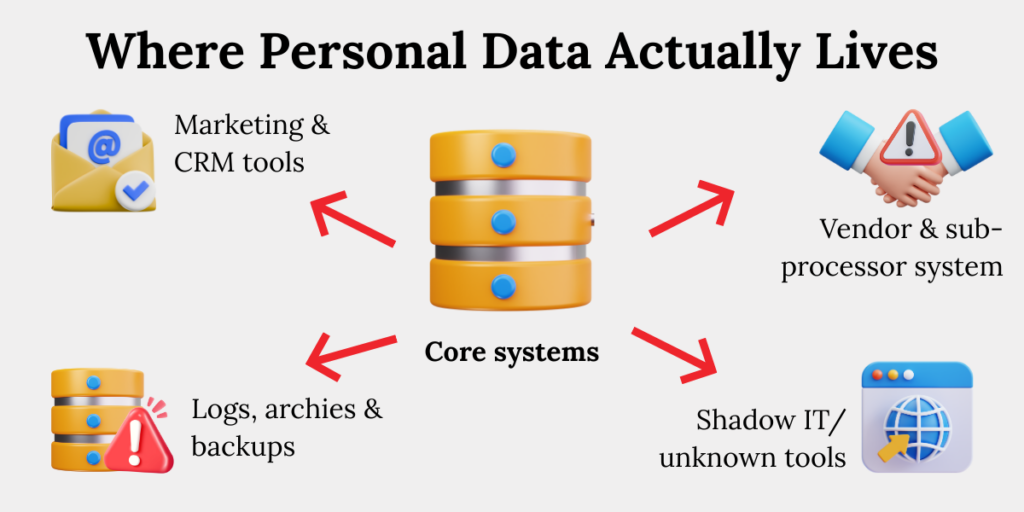

Mistake 2: Not Knowing Where All Personal Data Lives

Incomplete data inventories are a leading cause of privacy non-compliance. Without visibility into systems, vendors, logs, and shadow tools, organisations cannot meet obligations for access, correction, breach notification, or erasure – making compliance claims unverifiable.

You can’t defend what you can’t see.

In real audits, the biggest red flag isn’t a missing policy – it’s unknown data stores. Teams account for core databases but forget exports, email attachments, SaaS tools, analytics platforms, and vendor systems.

Where data hides

- Marketing and CRM tools

Personal data is often replicated across marketing automation platforms, CRM systems, and campaign tools, creating parallel data stores that are rarely tracked centrally. - Cloud storage and shared drives

- Logs, archives, and system backups

Application logs, debug files, and archived datasets often contain personal data and are excluded from formal inventories, despite being retained long-term. - Vendor and sub processor environments

Data sent to vendors continues to exist beyond the organisation’s direct control, especially when sub processors and offshore teams are involved.

Build visibility:

- Maintain a live data inventory

Replace static spreadsheets with continuously updated inventories that reflect real-time systems, integrations, and vendors. - Classify data by sensitivity and purpose

- Assign ownership and retention rules

Every data asset must have a responsible owner and a defined retention timeline to prevent indefinite storage

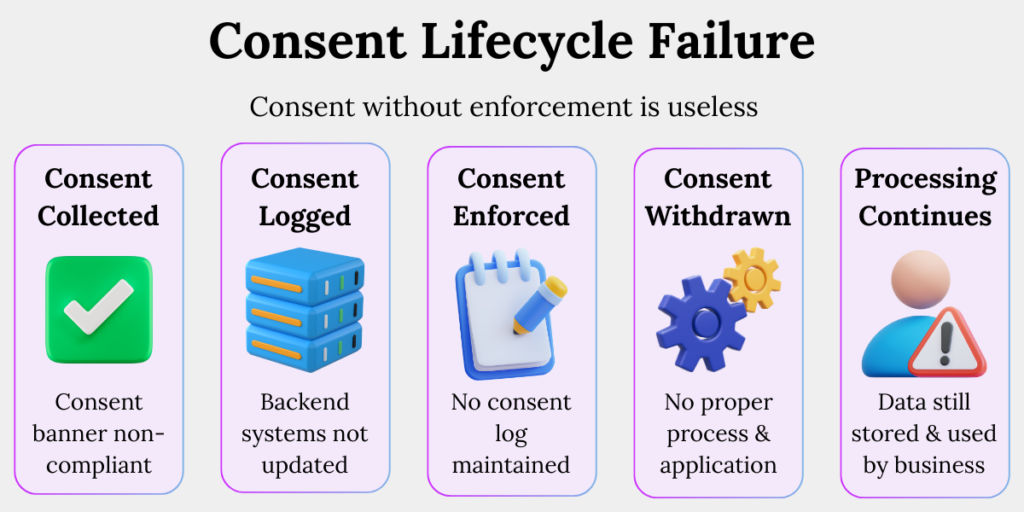

Mistake 3: Treating Consent as a Checkbox Exercise

Consent failures occur when organisations collect consent but fail to manage it dynamically. Regulators expect consent to be specific, revocable, logged, and enforced across systems. Static consent records without operational linkage are considered ineffective safeguards.

Consent isn’t a screenshot.

It’s a control mechanism.

We’ve seen consent banners deployed flawlessly – while backend systems continue processing data long after consent is withdrawn.

Common consent gaps

- Withdrawals are not system-wide

When users withdraw consent, only the front-end reflects the change. Backend systems, analytics tools, and vendors continue processing the data uninterrupted. - Consent logs exist but are never reviewed

Organisations store consent records for compliance but never audit them against actual data processing activities to check for mismatches. - Vendors ignore consent status

Third parties continue processing personal data because consent signals are not shared or enforced beyond the organisation’s core systems.

Operationalise consent:

- Integrate consent with access controls

Systems must automatically allow or block processing based on current consent status, without manual intervention. - Propagate consent changes in real time

Withdrawal or modification of consent should cascade across all connected systems and vendors without delay - Audit consent against processing activities

Regularly compare consent logs with system activity to detect unauthorised processing early.

If withdrawal doesn’t stop processing, consent is an illusion.

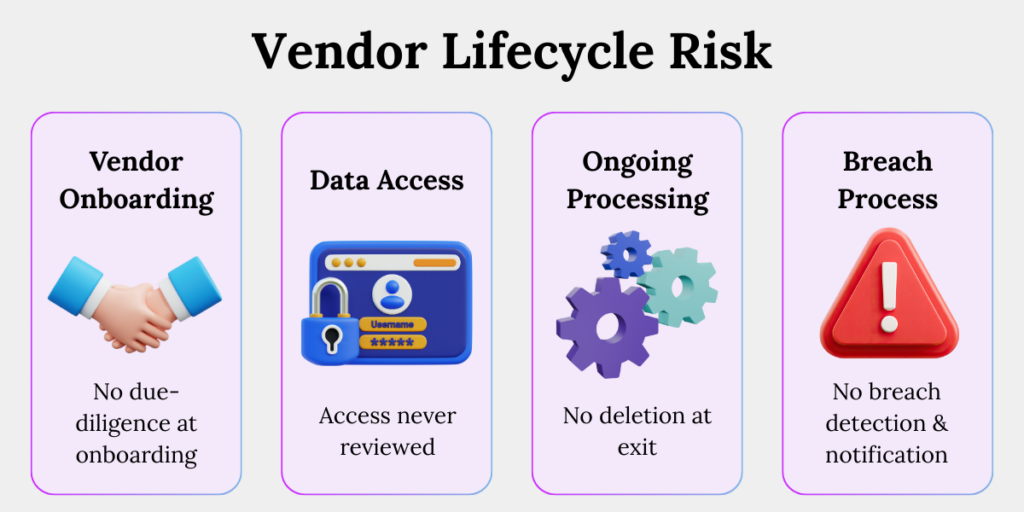

Mistake 4: Ignoring Vendor and Third-Party Risk

Third-party processing is one of the largest sources of privacy exposure. Regulators increasingly hold organisations accountable for vendor failures when contracts, oversight, and monitoring are inadequate. Vendor risk is now a core compliance obligation – not a procurement afterthought.

Your perimeter extends to your vendors.

In breach investigations, most often, the root cause isn’t an internal failure – it was a third party with excessive access and zero oversight.

Typical vendor failures

- No breach notification timelines

Contracts lack clear timelines for breach reporting, delaying regulatory notifications and increasing penalties. - Unclear deletion and return obligations

Vendors retain data indefinitely because contracts do not specify when and how data must be deleted or returned. - Over-privileged access and APIs

Vendors are granted broad system access that is never reviewed or revoked, increasing the attack surface over time.

Harden the supply chain:

- Maintain a live vendor register

Track all vendors, sub processors, data categories shared, and processing purposes in a central register. - Enforce privacy clauses contractually

Contracts must define breach reporting, deletion, access control, and audit rights clearly and be enforceable. - Review and revoke access periodically

Regularly reassess vendor access and disable unused accounts, credentials, and APIs.

Mistake 5: Keeping Data “Just in Case”

Excessive data retention increases breach impact and regulatory risk. Privacy laws require data to be retained only for defined purposes and durations. Organisations that hoard data without retention logic fail minimisation and storage limitation principles.

We regularly encounter datasets retained “for analytics,” “for future use,” or simply because no one owned deletion.

Data hoarding is a habit.

And like all bad habits, it needs to be broken.

Why this is dangerous

- Larger breach impact

The more data you retain, the more data is exposed during a breach, increasing harm to individuals and regulatory scrutiny. - Higher compliance penalties

Regulators assess whether retained data was necessary. Unjustified retention directly violates minimisation and storage limitation requirements. - Operational complexity increases

Excess data complicates access control, monitoring, and response efforts, making compliance harder over time.

Enforce discipline:

- Define clear retention schedules

Set purpose-based retention periods for each data category, aligned with legal and business requirements. - Trigger deletion automatically

Implement system-based deletion when the defined purpose ends, rather than relying on manual cleanup. - Review retention rules regularly

Periodically reassess whether retained data is still necessary and lawful.

Old data is rarely valuable, and always risky.

Mistake 6: Being Unprepared for a Data Breach

Breach response failures often stem from the absence of tested incident response plans. Regulators assess not just whether a breach occurred, but how quickly it was detected, contained, documented, and notified. Unprepared organisations amplify both harm and penalties.

Breaches don’t announce themselves.

Preparedness does.

And organisations with no rehearsal lose precious hours debating responsibilities instead of containing damage.

Breach readiness essentials

- Defined roles and escalation paths

Every team member should know their role, decision authority, and reporting lines before an incident occurs. - Tested response plans

Conduct regular tabletop exercises and simulations to identify gaps and improve coordination under pressure. - Clear documentation and timelines

Maintain detailed records of detection, decisions, containment, and notifications to demonstrate regulatory diligence

The first 72 hours decide outcomes.

Conclusion:

Data privacy compliance is not about looking compliant.

It’s about being defensible when scrutiny arrives.

The organisations that succeed treat privacy as architecture, not paperwork. They map data flows, enforce controls, audit continuously, and prepare for failure before it happens

If your current program relies on documents to explain gaps that systems cannot enforce, the fix is clear:

Rebuild the blueprint.

Reinforce the shield.

And close the data gates – before someone else walks in.

Key Takeaways

- Effective compliance requires shifting from “paper-thin” policies to robust technical controls that enforce privacy promises at the system level.

- Don’t just write a privacy policy; make sure your computer systems are actually set up to follow the rules you promised.

- You can’t protect what you don’t know exists; find and track all personal data sitting in emails, cloud drives, and old backups.

- If a user clicks “Unsubscribe” or “Delete,” your backend systems must stop using their data immediately and automatically.

- Your data is only as safe as the companies you share it with; regularly check their security and cancel access for those you no longer use.

- Keeping old data “just in case” is a massive risk; delete files the moment they are no longer needed for their original purpose.

- A data breach is a “when,” not an “if”; rehearse your response plan so everyone knows exactly what to do in the first 72 hours.